An extract from the book that riled India's Bharatiya Janata Party and led to the expulsion of its author Jaswant Singh, one of the founder members, of the party.

Comparing Gandhi and Jinnah is an extremely complex exercise but important for they were, or rather became, the two foci of the freedom movement. Gandhi was doubtless of a very different mould, but he too, like Jinnah, had gained eminence and successfully transited from his Kathiawari origins to become a London barrister before acquiring a political personality. Yet there existed an essential difference here. Gandhi's birth in a prominent family - his father was, after all, a diwan (prime minister) of an Indian state - helped immeasurably.

No such advantage of birth gave Jinnah a leg up, it was entirely through his endeavours. Gandhi, most remarkably, became a master practitioner of the politics of protest. This he did not do by altering his own nature, or language of discourse, but by transforming the very nature of politics in India. He transformed a people, who on account of prolonged foreign rule had acquired a style of subservience. He shook them out of this long, moral servitude. Gandhi took politics out of the genteel salons, the debating halls and societies to the soil of India, for he, Gandhi - was rooted to that soil, he was of it, he lived the idiom, the dialogue and discourse of that soil: its sweat; its smells and its great beauty and fragrances, too.

Some striking differences between these two great Indians are lucidly conveyed by Hector Bolitho in In Quest of Jinnah. He writes: 'Jinnah was a source of power'. Gandhi... an 'instrument of it... Jinnah was a cold rationalist in politics - he had a one track mind, with great force behind it'. Then: 'Jinnah was potentially kind, but in behaviour extremely cold and distant.' Gandhi embodied compassion - Jinnah did not wish to touch the poor, but then Gandhi's instincts were rooted in India and life long he soiled his hands in helping the squalid poor.

Showing posts with label British India. Show all posts

Showing posts with label British India. Show all posts

Mr. Jinnah before the Joint Select Committee

.

In 1911 the Joint Select Committee of the Parliament in London asked Mr. Jinnah the question:

“How do you justify an advance in self-government with a literacy percentage of only 12?”

Mr. Jinnah replied:

“Did the lack of literacy prevent you from going ahead with your successive Reforms Acts which continuously enlarged the franchise? And if it is good for England why should it be bad for India?”

.

.

In 1911 the Joint Select Committee of the Parliament in London asked Mr. Jinnah the question:

“How do you justify an advance in self-government with a literacy percentage of only 12?”

Mr. Jinnah replied:

“Did the lack of literacy prevent you from going ahead with your successive Reforms Acts which continuously enlarged the franchise? And if it is good for England why should it be bad for India?”

.

.

The Jinnah Cap

One piece of attire has long symbolised Pakistan’s national ideology: the Jinnah cap. Technically known as the Qaraqul cap, for it is made from the fur of the Qaraqul breed of sheep, the hat is typically worn by Central Asian men (presently, Afghan President Hamid Karzai is rarely seen without his). But in Pakistan, the hat has been firmly identified with the Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah for decades. This affiliation has ensured that others who sport the cap are understood to be making a political, rather than fashion, statement. Indeed, as Pakistan’s democratic fortunes have waxed and waned over the years, the choice by certain politicians to don the Jinnah cap has revealed much about political aspirations and the public mood.

The Jinnah cap was first initiated into national politics in 1937, when Jinnah sported it at the Lucknow session of the All India Muslim League on October 15. The cap was part of a complete change in Jinnah’s wardrobe; he surrendered his Saville Row suits in favour of a sherwani and Qaraqul cap meant to signify his commitment to the idea of a separate nation for the Muslims of South Asia.

Interestingly, at that point, many regarded the Jinnah cap as an answer to the hand-spun cotton cap which Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru used to wear, and which had come to symbolise the Congress Party’s ideals at the time.

Since then, the cap has graced many a brow vying for a successful political, even religious, career in the Land of the Pure. The cap has come to acquire ample political significance and is bought usually by oath-takers as a ritual to achieve the ‘crowning touch.’ In most cases, however, the cap’s symbolism has not proved powerful enough to achieve the degree of leadership success that Jinnah managed.

The Jinnah cap was first initiated into national politics in 1937, when Jinnah sported it at the Lucknow session of the All India Muslim League on October 15. The cap was part of a complete change in Jinnah’s wardrobe; he surrendered his Saville Row suits in favour of a sherwani and Qaraqul cap meant to signify his commitment to the idea of a separate nation for the Muslims of South Asia.

Interestingly, at that point, many regarded the Jinnah cap as an answer to the hand-spun cotton cap which Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru used to wear, and which had come to symbolise the Congress Party’s ideals at the time.

Since then, the cap has graced many a brow vying for a successful political, even religious, career in the Land of the Pure. The cap has come to acquire ample political significance and is bought usually by oath-takers as a ritual to achieve the ‘crowning touch.’ In most cases, however, the cap’s symbolism has not proved powerful enough to achieve the degree of leadership success that Jinnah managed.

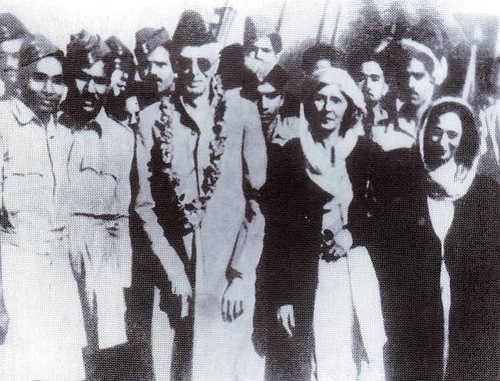

The Tense State Drive, Karachi 14 August 1947

.

Despite a warning from a British CID of a plot to assassinate Jinnah during this ride, the program proceeded on schedule. Mountbatten joined Jinnah on this ride from Victoria Road till Government House. The ride was most tense when passing through a Hindu neighbourhood which had little to rejoice and where the plotters were supposed to act. On reaching Government House, Jinnah kept his hand on Mountbatten's thigh and remarked, 'Thank God I brought you back alive'. 'I brought you back alive' retorted Mountbatten. Later on it was learnt that one of the conspirators lost his nerve at the crucial time. Did someone say Advani?

.

|

| Click on the image to enlarge |

Despite a warning from a British CID of a plot to assassinate Jinnah during this ride, the program proceeded on schedule. Mountbatten joined Jinnah on this ride from Victoria Road till Government House. The ride was most tense when passing through a Hindu neighbourhood which had little to rejoice and where the plotters were supposed to act. On reaching Government House, Jinnah kept his hand on Mountbatten's thigh and remarked, 'Thank God I brought you back alive'. 'I brought you back alive' retorted Mountbatten. Later on it was learnt that one of the conspirators lost his nerve at the crucial time. Did someone say Advani?

.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Gandhi and Jinnah - a study in contrasts

An extract from the book that riled India's Bharatiya Janata Party and led to the expulsion of its author Jaswant Singh, one of the foun...

-

We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one State. ( Presidential Address to the Co...

-

Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creat...

-

Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the voice of one hundred million Muslims, fought for their religious, social and economic freedom. Through...