The Pakistan Concept: Its Background

by P.H.L. Eggermont

Introduction

In 1936 Pandit Nehru wrote in his Autobiography :

Which mysterious forces may have caused the blind spot in the eyes of Nehru, and in the eyes of so many prominent Western intellectuals so that they failed to discern the strength of the Pakistan-concept?

The answer to that question lies hidden within a complexity of factors among which the most important one is the wide gap separating the Islamic and Hindu views regarding social, cultural and religious aspects of life.

As a matter of fact only the British have realized the unity of the sub-continent, and were able to guard it for over a century. In this respect Queen Victoria (1837-1904) was historically the first geographic Chakravartin. As, therefore, in the recent period the political unity of India happened to coincide with the traditional Hindu claim upon its ruling over the entire sub-continent, I am inclined to consider this mere coincidence to represent one among the factors which caused men like Nehru and Gandhi to close their eyes to the lesson of history teaching that partition and division had been the usual feature of the sub-continent for ages and ages.

Another mythical factor is the so-called “Absorption-theory”. In his book “Discovery of India” Nehru writes:-

“India’s peculiar feature is absorption, synthesis”. It is true, in antiquity this theory fitted in well with the facts: invaders like the Greeks in the 3rd century B.C., the Scythian in the 1st century B.C., the White Huns in the 5th century A.D., have been absorbed all of them.

The Muslims, however, are the exception to the rule. They have never been absorbed, though a great range of forms of peaceful co-existence can be noticed during the Muslim period.

How unacquainted the early Muslims were with the Indian culture is shown in the next lines written by Al-Beruni, the contemporary of Mahmud of Ghazni, who conquered the Punjab between A.D 1000 and 1026:-

“We believe in nothing in which they believe and vice-versa…. If ever a custom of theirs resembles one of ours, it has certainly just the opposite meaning”

Al-Beruni’s words seem to have remained valid until our days, for Mohammad Ali Jinnah, whose Centenary is celebrated at present, has explained during an interview in 1942 :-

In between Al-Beruni’s first notes on Indian creed and customs and the interview of Mohammad Ali Jinnah extends the gap of time filled by the autumn-time of the Indian Middle Ages, the preponderance of the Turco-Afghan states, the Empire of the Moghuls, and since A.D 1757 the power of the British Empire.

At first the British continued making use of the feudal structure of the Muslim and Hindu states they had conquered, ruling by means of the administrative Hindu middle class, and maintaining Persian as the language used in the courts of justice. The great change started only in the frame of the rise of liberalism and the big industries in England. Lord William Bentinck the first Governor-General of the entire sub-continent (A.D.1828-1835) replaced Persian by English, a reform of which he himself did not realize the importance, but which in the long run appear to have accelerated the modern development of the sub-continent a great deal. At first this reform was disadvantageous to the Muslims. The Hindus were quick to learn the new language, but they kept sticking to the use of charming Persian and useful Urdu so that they came to lag behind compared with the Hindus. Of 240 Indian pleaders admitted to the Calcutta bar between 1852 and 1868 only one was Muslim. The “Mutiny” of 1857 turned out to be disadvantageous to the Muslims as well. For a long time they were not permitted to follow a glorious career in the Indian army.

However, only thirty years later, in 1888, Lord Dufferin addressed the members the Mohammedan National League at Calcutta as follows:-

“In any event, be assured, Gentlemen, that I highly value those remarks of sympathy and approbation which you have been pleased to express in regard to the general administration of the country. Descended as you are from those who formerly occupied such a commanding position in India, you are exceptionally able to under-stand the responsibility attaching to those who rule.”

The scholar: Sir Syed Ahmad Khan

This Muslim renaissance, this recovery of Muslim political influence was almost entirely due to one Muslim whose indefatigable energy pointed his co-religionists the way to modern times. He was Sir Syed Ahmad (1817-1898). Starting his career as a clerk in the service of the East India Company in 1837 he finished as a member of the Governor General’s Legislative Council from 1878-1883. He had earned the confidence of the British by his saving many Europeans during the “Mutiny “, so that he was able to make the new rulers acquainted with the Muslim points of view they had been unaware of formerly. His activities comprised three fields, Islam, reconciliation with the British, and relation with the Hindus. As to Islam, after a visit to England in 1869 he became aware that Islamic theology should recover the dynamism it had possessed in the glorious past. In the same way as Islamic philosophy has amalgamated the scientific discoveries of the ancient Greek science during the middle Ages, it should react upon the new data provided by the recent Western science. There is no contradiction between the Word of Allah and the Work of Allah, he said. He spent much time to justify his effort by writing in two journals he had founded. His greatest contribution however was the establishment of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh where besides the study of Islam young Muslims could obtain English education. Many later political leaders as capable as the Hindus have studied there. Politically he preached firm loyalty to the British Crown so that he extricated the Muslims from their isolated position. His policy towards the Hindus was characterized by some distrust. When Lord Ripon created local self-government institutions he insisted that the Muslim communities should receive separate nomination.

This Muslim renaissance, this recovery of Muslim political influence was almost entirely due to one Muslim whose indefatigable energy pointed his co-religionists the way to modern times. He was Sir Syed Ahmad (1817-1898). Starting his career as a clerk in the service of the East India Company in 1837 he finished as a member of the Governor General’s Legislative Council from 1878-1883. He had earned the confidence of the British by his saving many Europeans during the “Mutiny “, so that he was able to make the new rulers acquainted with the Muslim points of view they had been unaware of formerly. His activities comprised three fields, Islam, reconciliation with the British, and relation with the Hindus. As to Islam, after a visit to England in 1869 he became aware that Islamic theology should recover the dynamism it had possessed in the glorious past. In the same way as Islamic philosophy has amalgamated the scientific discoveries of the ancient Greek science during the middle Ages, it should react upon the new data provided by the recent Western science. There is no contradiction between the Word of Allah and the Work of Allah, he said. He spent much time to justify his effort by writing in two journals he had founded. His greatest contribution however was the establishment of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh where besides the study of Islam young Muslims could obtain English education. Many later political leaders as capable as the Hindus have studied there. Politically he preached firm loyalty to the British Crown so that he extricated the Muslims from their isolated position. His policy towards the Hindus was characterized by some distrust. When Lord Ripon created local self-government institutions he insisted that the Muslim communities should receive separate nomination.

This distrust sprang notably from anti-Islamic currents among the Hindus, as e.g. it appeared from the popular novel Anandamath written by the Bengali author Bankim Chandra Chartterjee in 1882. The contents of this novel represented an affront to good taste in general and an insult to the Muslim community in particular. These anti-Islamic currents were not universal at the time. At the first session of the Indian National Congress held in 1886 the President said:

In fact it is this antithesis between the idealistic Hindu One-Nation theory and the realistic Muslim Two-Nation theory which contained the seed of the separation realized more than 60 years later.

The Poet: Mohammad Iqbal

Sir Syed had rendered the Indian Muslims their prestige, but the 20th century needed someone who gave them a sense of separate destiny. The Hindus were so fortunate as to obtain at an early time, in 1918, a charismatic leader, Mahatma Gandhi. In their turn the Muslims acquired a gifted and inspiring poet. They had to wait until 1936 before a leader turned up who was acknowledged by all of them. The poet was Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938). As a student in Europe (1905-1907) he had discerned the portents of the approaching World-war I. He returned to India, filled with dislike for the selfish policy of the European national sates, but also with admiration for the active, and dynamic life of the Europeans themselves. During the war he published his vision on the relation between individual man, the world and God (1915 and 1918). Some people, he says, regard the development of the individual as supreme end, and the state as an instrument to that. Others exalt the state and regard it as far more important than the rights of the individual. Between these extremes Iqbal shows the middle way, viz. the development of the spiritual person in close connection with the communal group to which one belongs. Such an ideal society however, is only possible if it is based on Monotheism, Tawhid, for the idea of one God emphasises the essential unity of all mankind. The human society is one indivisible unit and man is related to man as brother, irrespective of colour, creed or race or geographical environment. Therefore he says:-

It is with a view to the creation of a Muslim Home-land meant to representing a spiritual centre in support of the other Muslims scattered over the remaining portion of the Indian sub-continent, that Iqbal said at the Session of the Muslim League in 1930 :-

In 1933 a Muslim student at Cambridge, Chaudhari Rahmat Ali, proposed to give Iqbal’s project the name of Pakistan. The name struck the imagination of the masses, and was in general use as late as 1940.

The Leader: Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Iqbal was a poet, but no real politician. In fact the Muslims had at their disposal a qualified politician, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948), but he followed for a very long period the unitary point of view adhered to by Nehru and Gandhi until, at last , he was converted to the Pakistan concept in 1937. The reason may be sought for in his character on the one hand, and in the political situation on the other.

Jinnah was known as an incorruptible and very strict lawyer. A glimpse of his character appears perhaps from the next words he said in a speech held at Lucknow in 1937:-

“Think one hundred times before you take a decision, but once a decision is taken, stand by it as one man. “

When Muhammad Ali Jinnah started his political career, the Muslim League had got involved in the Khilafat Movement which dominated the political field from 1912 until 1924. In general the Indian Muslims tended to regard the Sultan of Turkey as the leader of the Islamic faith, though formerly, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan had said:

“You are the subjects of the British authority, and not those of Abdul Hamid.”

World-war I had turned the British Empire into the adversary of Turkey, and the harsh condition of its peace settlement had, for once, brought the Indian Muslims into line with Gandhi’s opposition against the British. It is why Mohammad Ali Jinnah as the then president of the Muslim League, and the National Congress signed the famous Lucknow Pact in 1916/1917. It was an agreement between the parties on the future Constitution of India according to which the Muslims were to have one third elective seats in the All Indian Legislature, and very reasonable percentages of the elective seats in the various provinces. In this respect one should realize that the strict and incorruptible lawyer Jinnah regarded the Lucknow Pact as a legal act, as a valid cheque on the future, and certainly not as a playing ball created by the political parties to play with of their own accord.

It is from the same point of view why he opposed Gandhi’s resolution of starting a peaceful non-co operation movement at the Nagpur session of the Indian National Congress in 1920. At the Conference there were 1050 Muslims among the 14582 delegates, but Muhammad Ali Jinnah was the only dissentient.

In a letter to Gandhi he wrote:-

The events of august 1921 proved how accurately Jinnah had judged the situation. The Islamic Moplahs of Malabar rose in revolt, murdered a few British administrative officers, finally turned against the Hindu landowners and money-lenders. Gandhi called off his peaceful non-co-operation movement, but preaching peace the had introduced the sword. Between 1920 and 1940 continued the series of the actions and counteractions between Muslims and Hindus which contemporaries like I myself used to read in the journals all over the world at the time.

Jinnah lost his influence in the National Congress, and, disgusted, he left India to establish himself as a lawyer in London between 1930-1940. There he was favoured by participation in the Round Table Conference of 1930-1931, where he met his famous co-religionist Muhammad Iqbal.

The result of this Round Table Conference was the 1935 Government of India Act, an impressive, but very intricate piece of work the most notable feature of which was the introduction of elections for 11 new Provincial Assemblies provided with their own responsible ministers.

In this connection Liaqat Ali Khan urged Jinnah to leave England in order to prepare the elections of 1937. Reminding his Muslim electorate of the Lucknow Pact 1916-17 he brought forward a moderate election programme. However, as the Muslim League was still a middle-class organization without a firm grip on the masses the elections became a brilliant success of the Congress party, which won the majority in 5 Provinces, and turned out to become the largest party in 2 others. Without any regard to Jinnah’s co-operation programme Nehru formed Congress ministries in the Hindu-Majority provinces where the Muslim League had captured a substantial number of the Muslim seats. In Uttar Pradesh the Congress went even so far as to propose that Leaguers would be taken into the Cabinet only if the League dissolved its parliamentary organization and if all its representatives became members of the Congress. This was what later on Sir Percival Griffiths called “a serious tactical blunder of Nehru”. It was even worse than that. Jinnah regarded it as treason to the Lucknow Pact, and he declared:-

On Iqbal’s advice Jinnah started to turn the League into a party of the masses. He reduced the annual membership to two annas. In the same way as Nehru and Gandhi he travelled all over the country conducting a fiery campaign. The number of his followers rose quickly and between 1938 and 1942 the League won 46 out of 56 by-elections in the Muslim constituencies throughout the provinces. He became the Quaid-i-Azam, the Great Leader, and against the Congress’s point of view that only the Congress represented the people of All-India, he was now able to put his counter-claim that the League, and only the League, could represent the Indian Muslims.

On 23rd March 1940 he took the final step leading to autonomy and separation. At the annual session of the League at Lahore the next resolution was accepted:-

The political correspondents of the press were quick to grasp the significance of this intricate long phrase, and they called it the “Pakistan resolution.”

When the long valley of World-War II was passed the political strife, or better the civil war, between Hindus and Muslims exploded, together with its horrible consequences. It ended in the replacement of Lord Wavell by Lord Mountbatten, the shock therapy by Mr. Attlee, who established the month of June 1947, and later on the 15th of August 1947 as the date of the transfer of power. It ended in the dramatic migration of 14,000,000 people, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs as well, perhaps the most massive simultaneous migration known in the history of the world. On 7th of August Jinnah flew to his native town Karachi. He was 71 years of age by now. On 11th of August he opened in his capacity of Governor General the first session of the Constituent Assembly of the recently created autonomous and independent State of Pakistan, and spoke:-

“You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any place of worship in the State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion, or caste or creed that has nothing to do with the fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of our State…Now, I think we should keep that in front of us and as ideal…”

P.H.L. Eggermont is the Professor at the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium.

Source: World Scholars on Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Edited by: Ahmad Hasan Dani, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 1979.

Introduction

In 1936 Pandit Nehru wrote in his Autobiography :

“The Muslim nation in India- a nation within a nation, and not even compact, but vague, spread out, indeterminate. Politically the idea is absurd. Economically it is fantastic; it is hardly worth considering….”At the time not only Nehru and his followers but also the greater part of the Western authors, journalists, and political reporters were sceptic, or even opposite to the Pakistan-concept. However, in spite of all these ominous prediction Pakistan became a fact on the 14th August 1947, and, at present, nearly thirty years after, it is manifest that this state has energetically survived wars and calamities, has courageously resisted economic reverse, and has developed into an esteemed member of the United Nations.

Which mysterious forces may have caused the blind spot in the eyes of Nehru, and in the eyes of so many prominent Western intellectuals so that they failed to discern the strength of the Pakistan-concept?

The answer to that question lies hidden within a complexity of factors among which the most important one is the wide gap separating the Islamic and Hindu views regarding social, cultural and religious aspects of life.

As a matter of fact only the British have realized the unity of the sub-continent, and were able to guard it for over a century. In this respect Queen Victoria (1837-1904) was historically the first geographic Chakravartin. As, therefore, in the recent period the political unity of India happened to coincide with the traditional Hindu claim upon its ruling over the entire sub-continent, I am inclined to consider this mere coincidence to represent one among the factors which caused men like Nehru and Gandhi to close their eyes to the lesson of history teaching that partition and division had been the usual feature of the sub-continent for ages and ages.

Another mythical factor is the so-called “Absorption-theory”. In his book “Discovery of India” Nehru writes:-

“India’s peculiar feature is absorption, synthesis”. It is true, in antiquity this theory fitted in well with the facts: invaders like the Greeks in the 3rd century B.C., the Scythian in the 1st century B.C., the White Huns in the 5th century A.D., have been absorbed all of them.

The Muslims, however, are the exception to the rule. They have never been absorbed, though a great range of forms of peaceful co-existence can be noticed during the Muslim period.

How unacquainted the early Muslims were with the Indian culture is shown in the next lines written by Al-Beruni, the contemporary of Mahmud of Ghazni, who conquered the Punjab between A.D 1000 and 1026:-

“We believe in nothing in which they believe and vice-versa…. If ever a custom of theirs resembles one of ours, it has certainly just the opposite meaning”

Al-Beruni’s words seem to have remained valid until our days, for Mohammad Ali Jinnah, whose Centenary is celebrated at present, has explained during an interview in 1942 :-

“Islam is not merely a religious doctrine, but a realistic and practical code of conduct - in terms of everything important in life, of our history, our heroes, our art, our architecture, our music, our laws, our jurisprudence. In all these things our outlook is not only fundamentally different, but often radically antagonistic to the Hindus.”

In between Al-Beruni’s first notes on Indian creed and customs and the interview of Mohammad Ali Jinnah extends the gap of time filled by the autumn-time of the Indian Middle Ages, the preponderance of the Turco-Afghan states, the Empire of the Moghuls, and since A.D 1757 the power of the British Empire.

At first the British continued making use of the feudal structure of the Muslim and Hindu states they had conquered, ruling by means of the administrative Hindu middle class, and maintaining Persian as the language used in the courts of justice. The great change started only in the frame of the rise of liberalism and the big industries in England. Lord William Bentinck the first Governor-General of the entire sub-continent (A.D.1828-1835) replaced Persian by English, a reform of which he himself did not realize the importance, but which in the long run appear to have accelerated the modern development of the sub-continent a great deal. At first this reform was disadvantageous to the Muslims. The Hindus were quick to learn the new language, but they kept sticking to the use of charming Persian and useful Urdu so that they came to lag behind compared with the Hindus. Of 240 Indian pleaders admitted to the Calcutta bar between 1852 and 1868 only one was Muslim. The “Mutiny” of 1857 turned out to be disadvantageous to the Muslims as well. For a long time they were not permitted to follow a glorious career in the Indian army.

However, only thirty years later, in 1888, Lord Dufferin addressed the members the Mohammedan National League at Calcutta as follows:-

“In any event, be assured, Gentlemen, that I highly value those remarks of sympathy and approbation which you have been pleased to express in regard to the general administration of the country. Descended as you are from those who formerly occupied such a commanding position in India, you are exceptionally able to under-stand the responsibility attaching to those who rule.”

The scholar: Sir Syed Ahmad Khan

This Muslim renaissance, this recovery of Muslim political influence was almost entirely due to one Muslim whose indefatigable energy pointed his co-religionists the way to modern times. He was Sir Syed Ahmad (1817-1898). Starting his career as a clerk in the service of the East India Company in 1837 he finished as a member of the Governor General’s Legislative Council from 1878-1883. He had earned the confidence of the British by his saving many Europeans during the “Mutiny “, so that he was able to make the new rulers acquainted with the Muslim points of view they had been unaware of formerly. His activities comprised three fields, Islam, reconciliation with the British, and relation with the Hindus. As to Islam, after a visit to England in 1869 he became aware that Islamic theology should recover the dynamism it had possessed in the glorious past. In the same way as Islamic philosophy has amalgamated the scientific discoveries of the ancient Greek science during the middle Ages, it should react upon the new data provided by the recent Western science. There is no contradiction between the Word of Allah and the Work of Allah, he said. He spent much time to justify his effort by writing in two journals he had founded. His greatest contribution however was the establishment of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh where besides the study of Islam young Muslims could obtain English education. Many later political leaders as capable as the Hindus have studied there. Politically he preached firm loyalty to the British Crown so that he extricated the Muslims from their isolated position. His policy towards the Hindus was characterized by some distrust. When Lord Ripon created local self-government institutions he insisted that the Muslim communities should receive separate nomination.

This Muslim renaissance, this recovery of Muslim political influence was almost entirely due to one Muslim whose indefatigable energy pointed his co-religionists the way to modern times. He was Sir Syed Ahmad (1817-1898). Starting his career as a clerk in the service of the East India Company in 1837 he finished as a member of the Governor General’s Legislative Council from 1878-1883. He had earned the confidence of the British by his saving many Europeans during the “Mutiny “, so that he was able to make the new rulers acquainted with the Muslim points of view they had been unaware of formerly. His activities comprised three fields, Islam, reconciliation with the British, and relation with the Hindus. As to Islam, after a visit to England in 1869 he became aware that Islamic theology should recover the dynamism it had possessed in the glorious past. In the same way as Islamic philosophy has amalgamated the scientific discoveries of the ancient Greek science during the middle Ages, it should react upon the new data provided by the recent Western science. There is no contradiction between the Word of Allah and the Work of Allah, he said. He spent much time to justify his effort by writing in two journals he had founded. His greatest contribution however was the establishment of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh where besides the study of Islam young Muslims could obtain English education. Many later political leaders as capable as the Hindus have studied there. Politically he preached firm loyalty to the British Crown so that he extricated the Muslims from their isolated position. His policy towards the Hindus was characterized by some distrust. When Lord Ripon created local self-government institutions he insisted that the Muslim communities should receive separate nomination.This distrust sprang notably from anti-Islamic currents among the Hindus, as e.g. it appeared from the popular novel Anandamath written by the Bengali author Bankim Chandra Chartterjee in 1882. The contents of this novel represented an affront to good taste in general and an insult to the Muslim community in particular. These anti-Islamic currents were not universal at the time. At the first session of the Indian National Congress held in 1886 the President said:

“For long our fathers lived and we have lived as individuals only or as families, but henceforward I hope that we shall be living as a nation, united one and all to promote our welfare, and the welfare of our mother-country”.Sir Syed however did not agree to that, and called the members of the Congress back to reality by saying in one of his speeches on the subject:-

“The proposals of the Congress are exceedingly inexpedient for a country which is inhabited by two different nations….Now suppose that all the English …were to leave India….then who would be rulers of India? Is it possible that under these circumstances two nations---the Mohammedan and Hindu—could sit on the same throne and remain equal in power? Most certainly not. It is necessary that one of them should conquer the other and thrust it down. To hope that both could remain equal is to desire the impossible and the inconceivable.”

In fact it is this antithesis between the idealistic Hindu One-Nation theory and the realistic Muslim Two-Nation theory which contained the seed of the separation realized more than 60 years later.

The Poet: Mohammad Iqbal

Sir Syed had rendered the Indian Muslims their prestige, but the 20th century needed someone who gave them a sense of separate destiny. The Hindus were so fortunate as to obtain at an early time, in 1918, a charismatic leader, Mahatma Gandhi. In their turn the Muslims acquired a gifted and inspiring poet. They had to wait until 1936 before a leader turned up who was acknowledged by all of them. The poet was Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938). As a student in Europe (1905-1907) he had discerned the portents of the approaching World-war I. He returned to India, filled with dislike for the selfish policy of the European national sates, but also with admiration for the active, and dynamic life of the Europeans themselves. During the war he published his vision on the relation between individual man, the world and God (1915 and 1918). Some people, he says, regard the development of the individual as supreme end, and the state as an instrument to that. Others exalt the state and regard it as far more important than the rights of the individual. Between these extremes Iqbal shows the middle way, viz. the development of the spiritual person in close connection with the communal group to which one belongs. Such an ideal society however, is only possible if it is based on Monotheism, Tawhid, for the idea of one God emphasises the essential unity of all mankind. The human society is one indivisible unit and man is related to man as brother, irrespective of colour, creed or race or geographical environment. Therefore he says:-

“That which leads to unison in a hundred individuals is but a secret from the secrets of Tawhid. Religion, wisdom and law are all the effects; power, strength and supremacy originate from it. Its influence exalts the slaves, and virtually creates a new species out of them. Within it fear and doubt depart, spirit of action revives, and the eye sees the very secret of the Universe.”

It is with a view to the creation of a Muslim Home-land meant to representing a spiritual centre in support of the other Muslims scattered over the remaining portion of the Indian sub-continent, that Iqbal said at the Session of the Muslim League in 1930 :-

“I would like to see the Punjab, North West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within the British Empire or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated North Western Indian Muslim state appear to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of North West India… The Muslim demand ..is actuated by a genuine desire for free development which is practically impossible under the type of unitary government contemplated by the nationalist Hindu politicians with a view to secure permanent communal dominance in the whole of India. Nor should the Hindus fear that the creation of autonomous Muslim states will mean the introduction of a kind of religious rule in such states. For India it means security and peace resulting from an internal balance of power, for Islam an opportunity to rid itself of the stamp that Arabian imperialism was forced to give it, to mobilize its law, its education, its culture, and to bring them into closer contact with its own original spirit and with the spirit of modern times.”

In 1933 a Muslim student at Cambridge, Chaudhari Rahmat Ali, proposed to give Iqbal’s project the name of Pakistan. The name struck the imagination of the masses, and was in general use as late as 1940.

The Leader: Muhammad Ali Jinnah

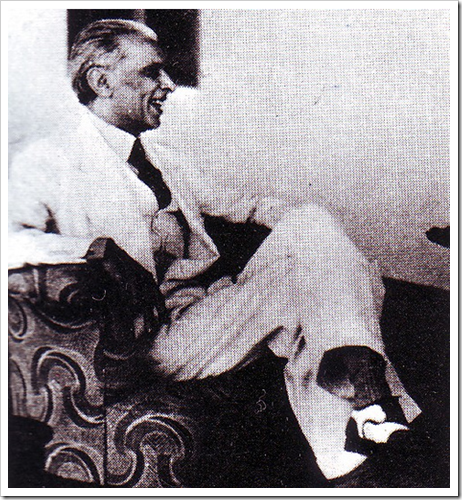

Iqbal was a poet, but no real politician. In fact the Muslims had at their disposal a qualified politician, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948), but he followed for a very long period the unitary point of view adhered to by Nehru and Gandhi until, at last , he was converted to the Pakistan concept in 1937. The reason may be sought for in his character on the one hand, and in the political situation on the other.

Jinnah was known as an incorruptible and very strict lawyer. A glimpse of his character appears perhaps from the next words he said in a speech held at Lucknow in 1937:-

“Think one hundred times before you take a decision, but once a decision is taken, stand by it as one man. “

When Muhammad Ali Jinnah started his political career, the Muslim League had got involved in the Khilafat Movement which dominated the political field from 1912 until 1924. In general the Indian Muslims tended to regard the Sultan of Turkey as the leader of the Islamic faith, though formerly, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan had said:

“You are the subjects of the British authority, and not those of Abdul Hamid.”

World-war I had turned the British Empire into the adversary of Turkey, and the harsh condition of its peace settlement had, for once, brought the Indian Muslims into line with Gandhi’s opposition against the British. It is why Mohammad Ali Jinnah as the then president of the Muslim League, and the National Congress signed the famous Lucknow Pact in 1916/1917. It was an agreement between the parties on the future Constitution of India according to which the Muslims were to have one third elective seats in the All Indian Legislature, and very reasonable percentages of the elective seats in the various provinces. In this respect one should realize that the strict and incorruptible lawyer Jinnah regarded the Lucknow Pact as a legal act, as a valid cheque on the future, and certainly not as a playing ball created by the political parties to play with of their own accord.

It is from the same point of view why he opposed Gandhi’s resolution of starting a peaceful non-co operation movement at the Nagpur session of the Indian National Congress in 1920. At the Conference there were 1050 Muslims among the 14582 delegates, but Muhammad Ali Jinnah was the only dissentient.

In a letter to Gandhi he wrote:-

“Your methods have already caused split and division in almost every institution that you have approached hitherto …people generally are desperate all over the country and your extreme programme has for the moment struck the imagination mostly of the inexperienced youth and the ignorant and the illiterate. All this means complete disorganization and chaos.”

The events of august 1921 proved how accurately Jinnah had judged the situation. The Islamic Moplahs of Malabar rose in revolt, murdered a few British administrative officers, finally turned against the Hindu landowners and money-lenders. Gandhi called off his peaceful non-co-operation movement, but preaching peace the had introduced the sword. Between 1920 and 1940 continued the series of the actions and counteractions between Muslims and Hindus which contemporaries like I myself used to read in the journals all over the world at the time.

Jinnah lost his influence in the National Congress, and, disgusted, he left India to establish himself as a lawyer in London between 1930-1940. There he was favoured by participation in the Round Table Conference of 1930-1931, where he met his famous co-religionist Muhammad Iqbal.

The result of this Round Table Conference was the 1935 Government of India Act, an impressive, but very intricate piece of work the most notable feature of which was the introduction of elections for 11 new Provincial Assemblies provided with their own responsible ministers.

In this connection Liaqat Ali Khan urged Jinnah to leave England in order to prepare the elections of 1937. Reminding his Muslim electorate of the Lucknow Pact 1916-17 he brought forward a moderate election programme. However, as the Muslim League was still a middle-class organization without a firm grip on the masses the elections became a brilliant success of the Congress party, which won the majority in 5 Provinces, and turned out to become the largest party in 2 others. Without any regard to Jinnah’s co-operation programme Nehru formed Congress ministries in the Hindu-Majority provinces where the Muslim League had captured a substantial number of the Muslim seats. In Uttar Pradesh the Congress went even so far as to propose that Leaguers would be taken into the Cabinet only if the League dissolved its parliamentary organization and if all its representatives became members of the Congress. This was what later on Sir Percival Griffiths called “a serious tactical blunder of Nehru”. It was even worse than that. Jinnah regarded it as treason to the Lucknow Pact, and he declared:-

“On the very threshold of what little power and responsibility is given, the Majority community have shown their hand, that Hinduism is for the Hindus. Only the Congress masquerades under the names of nationalism.”

On Iqbal’s advice Jinnah started to turn the League into a party of the masses. He reduced the annual membership to two annas. In the same way as Nehru and Gandhi he travelled all over the country conducting a fiery campaign. The number of his followers rose quickly and between 1938 and 1942 the League won 46 out of 56 by-elections in the Muslim constituencies throughout the provinces. He became the Quaid-i-Azam, the Great Leader, and against the Congress’s point of view that only the Congress represented the people of All-India, he was now able to put his counter-claim that the League, and only the League, could represent the Indian Muslims.

On 23rd March 1940 he took the final step leading to autonomy and separation. At the annual session of the League at Lahore the next resolution was accepted:-

“No constitutional plan would be workable in this country or acceptable to the Muslims unless it is designed on the following basic principles, viz. that geographically contiguous units are demarcated into regions which should be so constituted with such territorial adjustments as may be necessary, that the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in a majority, as in the north-western and eastern zones of India, should be grouped to constitute Independent States in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign.”

The political correspondents of the press were quick to grasp the significance of this intricate long phrase, and they called it the “Pakistan resolution.”

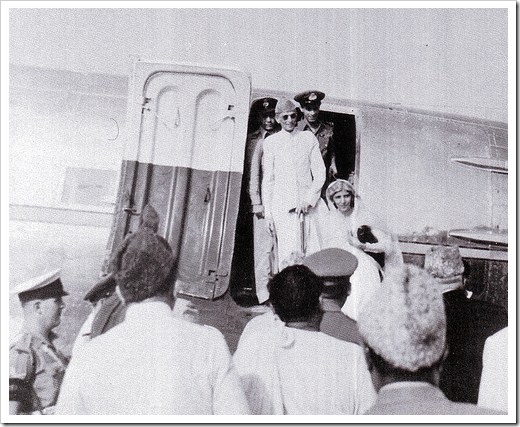

When the long valley of World-War II was passed the political strife, or better the civil war, between Hindus and Muslims exploded, together with its horrible consequences. It ended in the replacement of Lord Wavell by Lord Mountbatten, the shock therapy by Mr. Attlee, who established the month of June 1947, and later on the 15th of August 1947 as the date of the transfer of power. It ended in the dramatic migration of 14,000,000 people, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs as well, perhaps the most massive simultaneous migration known in the history of the world. On 7th of August Jinnah flew to his native town Karachi. He was 71 years of age by now. On 11th of August he opened in his capacity of Governor General the first session of the Constituent Assembly of the recently created autonomous and independent State of Pakistan, and spoke:-

“You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any place of worship in the State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion, or caste or creed that has nothing to do with the fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of our State…Now, I think we should keep that in front of us and as ideal…”

P.H.L. Eggermont is the Professor at the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium.

Source: World Scholars on Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Edited by: Ahmad Hasan Dani, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 1979.

Quaid-e-Azam and Pakistan's Foreign Policy

This paper suggests that Pakistan’s foreign policy under Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah represented a confluence of three variables: the Quaid’s world view or cosmology, the security compulsions of the new State of Pakistan and the cold war international system in which Pakistan had to conduct itself after its inception on 14 August 1947. Despite his failing health, the Quaid could find time to define the strategic parameters of Pakistan’s foreign policy according to his own predilections. Pakistan “did not have a full time Foreign Minister until December 1947” and “in practice all papers were put up to Quaid-i-Azam for information or decision.”1

The basic tenets of the foreign policy of the new State of Pakistan were outlined by Quaid-i-Azma at a press conference in Delhi on 14 July 1947. He remarked that the new state “will be most friendly to all nations. We stand for the peace of the world. We will make our contribution whatever we can.”2 These ideas were further explicated on 15 August, when as Governor-General of Pakistan, the Quaid observed:

Our objective should be peace within and peace without. We want to live peacefully and maintain cordial and friendly relations with our immediate neighbours and with world at large. We have no aggressive designs against any one. We stand by the United Nations Charter and will gladly make our contribution to the peace and prosperity of the world.3

Prefiguring the doctrine of non-alignment, the Quaid-i-Azam, in his broadcast talk to the people of the USA in February 1948 said:

Our foreign policy is one of the friendliness and goodwill towards all the nation of the world. We do not cherish aggressive designs against any country or nation. We believe in the principle of honesty and fair-play in national and international dealings, and are prepared to make our contribution to the promotion of peace and prosperity among the nations of the world. Pakistan will never be found lacking in extending its material and moral support to the oppressed and suppressed peoples of the world and in upholding the principles of the United Nations Charter.4

Quaid-i-Azam World View

World views are those core elements of human belief systems which act as organizing principles for ordering the universe of our perceptions of the social environment. They are stable but historical in nature and always reflect subjective understanding of the objective reality. World views provide fundamental assumptions about knowledge and action. World views are of two types: rationalistic and non-rationalistic. The former emphasize order, clarity, empiricism and logical analysis while the latter revolve around “novelty, incongruity, intuition and subjective awareness.”5 At the heart of the rationalistic world view is the dualistic notion that reality is both fundamentally orderly and empirically available. Thus, “all things can be completely understood and explained by means of logical analysis and empirical inquiry…..Life can be shaped and directed in accordance with human objectives and aspirations.”6

The Quaid-i-Azam’s worldview may be characterized as rationalistic. Such a characterization is warranted by the fact that “Jinnah’s appeal to religion was always ambigious, certainly it was not characteristic of his political style before 1937, and evidence suggests that his use of the communal factor was a political tactic, not an ideological commitment”. (emphasis added).7 It undoubtedly had a normative component in that it was geared towards the realization of the idea of Pakistan. What type of state did Jinnah have in mind? His address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on 11 August, 1947 offers a perspective:

If you change your past and work together in a spirit that everyone of you, no matter what community he belongs, no matter, what relations he had with you in the past, no matter what is his colour, caste or creed, is first, second and last a citizen of this State with equal rights, privileges and obligations there will be no end to the progress you will make. You should begin to work in that spirit and in course of time all these angularities of the majority and minority communities, the Hindu community and the Muslim community because even as regards Muslims you have Pathans, Punjabis, Shias, Sunnis and so on and among the Hindus you have Brahmins, Vashnavas Khatris, also Bengalese, Madrasis, and so on – will vanish. Indeed if you ask me this has been the biggest hindrance in the way of India to attain freedom and independence and but for this we would have been free people long ago….. You are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed that has nothing to do with the business of the State. We are starting with the fundamental principle that we all are citizens and equal citizens of one State….8

The same ideas of justice, equality and fairness also informed the Quaid’s thinking and politics regarding international issues. For example, on the emotionally charged issue of the Khilafat in Turkey in 1920, Jinnah as a true constitutionalist, “derided the false and dangerous religious frenzy” of the zealots, both Hindu and Muslim” since it threatened the stability of the existing political structures and orderly progress along moderate and nationalist lines.9 In 1937, following the rejection by the Arabs of the Peel Commission proposal that Palestine should be divided into Arab and Jewish State, leaving Britain with a mandate over a reduced area which would include the holy place of Jerusalem, Quaid-i-Azam expressed strong support for the Arab position and called upon London to honour its pledge of total independence to the Arab people. In his Presidential address to the All India Muslim League delivered at Lucknow on 16 October 1937, the Quaid stated:

Great Britain has dishonored her proclamation to the Arabs which had guaranteed to them complete independence of the Arab homeland and the formation of an Arab Confederation under the stress of the Great War….May I point out to Great Britain that this question of Palestine, if not fairly and squarely met, boldy and courageously decided, is gong to be a turning point in the history of the British Empire…..The Muslims of India will stand solidly and will help the Arabs in every way they can in their brave and just struggle that they are carrying on against all odds.10

The Quaid-i-Azam vehemently opposed the partition of Palestine and the establishment of Israel in 1948. In an interview to Mr. Robert Stimson, B.B.C. correspondent on 19 December 1947, the Quaid said,”…. Our sense of justice obliges us to help the Arab cause in Palestine in every way that is open to us.”11 Similarly in his reply to a telegram from the King of Yemen on 24 December 1947, Quaid-i-Azam expressed his “surprise and shock” all the UN decision to approve of the partition of Palestine. Describing the division of Palestine as “outrageous and inherently unjust” the Quaid assured “the Arab brethren” that “Pakistan will stand by them in their opposition to the UNO decision.”12 Later, Quaid-i-Azam sent a cable to President Truman urging him to “uphold the rights of the Arabs” and thus “avoid the greatest consequences and repercussions.”13 The Quaid-i-Azam gave open and unflinching support to North African Arabs in their struggle to throw off the French yoke. He considered the Dutch attack upon Indonesia as an attack on Pakistan itself and refused transit facilities to Dutch ship and planes, carrying war material to Indonesia.”14 Similarly, Pakisan provided all possible “diplomatic and material assistance to the liberation movement in Indonesia, Malaya, Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, Nigeria and Algeria.”15

Pakistan’s Security Compulsions

Soon after its emergence as an independent nation on 14 August 1947 Pakistan was faced with a hostile security environment. The most serious threat to Pakistan’s security emanated from India which never reconciled itself to the idea of the partition of the subcontinent. Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah too had strong reservations about the Radcliffe award which he characterized as “unjust, incomprehensible and even perverse.”16 This was mainly because the Punjab Boundary Commission had deprived Pakistan of “territories which, by all cannons of justice, should have gone to [it] – territories the possession of which enabled India to annex the Muslims majority states of Jammu and Kashmir.”17 Notwithstanding its unjust character, Quaid-i-Azam agreed to accept the decision of the Boundary Commission since as “honourable people” the Pakistan “had agreed to abide by it.”18 After the acceptance of the partition plan, Quaid-i-Azam expressed to the new India his friendly feelings and desire for full cooperation, even to the extent of “wishing for a joint defence plan.”19 Speaking at a Press Conference in New Delhi on 14 July 1947, he said that relations between India and Pakistan “will be friendly and cordial” since “being neighbours” “we can be of use to each other, not to say the world.”20 On August 15, 1947, as the first Governor General of Pakistan, the Quaid declared: “We want to live peacefully and maintain cordial relations with our immediate neighbours and with the world at large.”21 But the Indian inablilty to accept the ineluctable reality of the partition of the British India ensured that these early Pakistani hopes for friendly ties with India were cut short giving rise to the pessimistic belief that Pakistan, in the words of Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, had “been surrounded on all sides by forces which were to destroy her.”22 That the Indian leadership harboured grave reservations about the Partition Plan was evident from Jawaharlal Nehru’s following remarks: “The proposals to allow certain parts to secede if they so will is painful for any one of us to contemplate”.23 Expressing the similar view, the resolution of the All-India Congress Committee on the Paritition Plan, adopted on 15 June 1947 stated:

Geography and the mountains and the seas fashioned India as she is, and no human agency can change the shape or come in the way of her final destiny. Economic circumstances and the insistent demands of international affairs make the unity of India still more necessary. The picture of India we have learnt to cherish will remain in our minds and hearts. The A.I.C.C. earnestly trusts that when present passions have subsided, India’s problems will be viewed in their proper perspective and the false doctrine of the two nations in India will be discredited and discarded by all.24

In October 1947, Field Marshal Claude Auchinleck reprted to the British Prime Minister Attlee: “The present Indian cabinet are implacably determined to do all in their power to prevent the establishment of the Dominion of Pakistan on a firm basis.”25 In line with the policy of implacable hostility towards the new state of Pakistan, India forcibly occupied some Princely States in Kathiawar, which had acceded to Pakistan and secured accession of the State of Jammu Kashmir by manipulation. Further, it discontinued the supply of coal and withheld a part of Pakistan’s share in the cash balances, arms and equipment. The Indian Government failed to protect the lives and properties of a large number of Muslims and there was a heavy influx of Muslim refugees into Pakistan. In 1948 Pakistan fought the kashmir war and was faced with the prospect of Indian trying to “throttle and choke” it “at birth”.26 The conflict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir stemmed mainly from the selective application of the principles on which partition was based. British India had 562 princely states which on the eve of the British departure were given the option to join either India or Pakistan in keeping with their geography and the will of their inhabitants. With the exception of three princely states Junagarh, Hyderabad and the State of Jammu and Kashmir the choice was a simple one as they had to simply follow the dictates of their Muslim or Hindu heritage. In each of these three states the ruling family belonged to one religious community and the great majority of the population to the other. And this anomalous situation posed special problems. In Junagadh and Hyderabad, Muslim princes rules over the Hindu majority.

Similarly, Pakistan was confronted with the security problems in the North-West also where Afghanistan had made irredentist claims. As early as November 1944, the Afghanistan Government, anticipating that the British would have to relinquish power in India, made the representation to London that the people of those areas of North-West Frontier which had been annexed to Indian during the last century should be offered option of becoming independent or rejoining Afghanistan. The Afghanistan Government was pressing for the acceptance of its demands when in 1946 the Khudai Khidmatgar Movement, which was an ally of the Indian National Congress, raised the slogan of “Pakhtunistan.” The slogan then “signified an agitation or demands for independence of the Pathans of the North-West Frontier – Independence that is from Pakistan, should such a state come into being.” The Partition Plan provided that a referendum would be held in the North–West Frontier Province to ascertain whether the population of the area wanted to join Pakistan or India. The British Government rejected the Red Shirt proposal that there should also be an option for independence in the referendum as per coordination of 3 June 1947 plan.

The referendum was held in the NWFP in July 1947 without the requested addition of independence as an option for the Pashtuns. Out of the total electorate of 572,798 the valid votes cast for union with Pakistan were 289,244 while the remaining 2,074 were for union with India.27 The NWFP became part of Pakistan, on the basis of the referendum. The frontier States of Swat, Chitral, Dir and Amb also acceded to Pakistan, and the Tribal Jirgas of the frontier region opted for “attachment of the Tribal Agencies to Pakistan.”28 Afghanistan did not accept this arrangement whereas the British had to proceed to the Pakistan Plan agreed to between the British, Indian National Congress and All-India Muslim League. As follow up of the referendum the Quaid as Pakistan’s first Governor-General sacked Dr. Khan Sahib’s Ministry in the NWFP in the first week after the independence.

Afghanistan’s non-recognition of the NWFP and the Tribal Agencies as part of Pakistan coupled with the fact that Afghanistan was the only state that cast a negative vote on Pakistan’s application for membership to the UN in September 1947, caused a sense of deep resentment in Karachi. In November 1947, Najibullah Khan, special envoy of King Zahir Shah of Afghanistan, made three demands on Pakistan: “creation of free sovereign province’ comprising the tribal region; establishment of a corridor aeries West Baluchistan to give Afghanistan an access to the sea or, alternatively, granting a ‘free Afghan Zone’ in Karachi; and conclusion of a Pakistan Afganistan treaty specifically providing that either party could remain neutral in case the other party was attacked.”29

The hopes raised by Karachi talks of an amicable settlement of the Pakistan-Afghanistan difference proved to be unfounded. In June 1948 the Government of Pakistan arrested Abdul Ghaffar Khan and a score of other Pushtun leaders as a result of their subversive activities. These arrests were followed by the “intensification of Pakistani military action in the tribal areas (including the use of the air force against their tribal opponents.”30

The dilapidated condition of Pakistan’s armed forces31 and concern for its borders in the face of territorial disputes with its neighbours, India and Afghanistan, forced Karachi to turn away from South Asia for security assistance. Several other factors induced Karachi to look in the directions of the Western block, particularly the United States First. Pakistan’s ruling elite “hailing from the feudal and to some extend, commercial classes, the bureaucracy and the military” had a liking for the West due to its Western education and cultural outlook. The Quaid-i-Azam himself represented the best of Western education, throughout, cultural values and rationality. Secondly, Pakistan’s economy was integrated with the West, particularly Britain, during the colonial era and it would not have been easy to transform it along the socialist lines. Pakistan “preferred to have trading partners in the West because they were in a position to supply consumer goods at very competitive prices for local requirements and provided almost assured markets for Pakistan’s raw materials.”32 Thirdly, Pakistan expected strong Western diplomatic and political support from the United States and Great Britain in the settlement of its disputes with India. Finally, “the transfer of power by the British in the subcontinent to the Government of India and Pakistan had not brought about any immediate change in the Soviet opinion and, since the Soviet Union had apprehensions about the role of the decolonize nations in the world affairs, its own attitude was somewhat cool.”33

Barely two weeks after its inception, Pakistan’s Finance Minister, Ghulam Mohammad, during his informal talks wit the U.S. Charge d’Affairs, Chairles W. Lewis, Jr., sought capital and technical assistance for Pakistan on the ground that funds were needed to “meet the administrative approximately $2 billion over a period of five years. Immediately thereafter Pakistan submitted to the State Department the following breakdown of Pakistan’s requirement: $700 million for industrial development, $700 million for agricultural development and $510 million for building and equipping defense services. Further breakdown of the defence expenditure showed $170 million for the Navy and $205 million to meet the anticipated deficits in Pakistan’s military budget.34

These Pakistani appeals for urgent financial aid from Washington were greeted with vague promises bordering on ‘wait an see’ attitude. Several consideration underpinned this American reluctance to assume the role of a military benefactor for Karachi. The first was a continuation of Washington’s pre-independence desire to consult with London on matters of importance in South Asia. The second was Washington’s insistence on taking a regional approach to the areas which called for an evenhanded approach vis-à-vis controversies between Pakistan and India. The third factor was the American preoccupation with the European affairs and the consequent denigration of South Asia as an important strategic region. It was not until the fall of China to the Communists in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War a year later that the U.S. began to pay any serious heed to the South Asian region in terms of its emergent global strategy of the containment of the Communism.

Notes and References

- Saeeduddin Ahmed Dar, “Foreign Policy of Pakistan: 1947-48,” in Ahmed Hasan Dani, ed., World Scholars on Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Islamabad, 1979, p. 364.

- Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah: Speeches and Statements As Governor General of Pakistan 1947-1948, Islamabad, 1989, p. 29.

- Ibid. pp. 55-56.

- Ibid. pp. 157-158.

- Miriam Steiner, “The Speech for Order in a disorderly world: Worldviews and Prescriptive decision paradigms”, International Organization, 37:3, 1983, p. 37.

- Ibid.

- Ayesha Jalal, The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan, Cambridge, 1948, p. 5.

- Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Speeches, p.46.

- Jalal, pp. 8-9.

- Rizwan Ahmed, ed. Saying of Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah (Karachi: Elite Publishers, 1947), p. 86.

- Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah: speeches, p. 11.

- Ibid.

- Saeeduddin Ahmed Dar, “Foreign Policy of Pakistan: 1947-48,” in Ahmed Hasan Dani, ed., p. 362.

- S. Raza

- Ibid.

- Quoted in G.W. Choudhry, Pakistan’s Relations with India, 1947-1966, (London: Pall Mall Press, 1968), p. 56.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 40.

- Saying of Quaid-i-Azam, op. cit., p. 80.

- Choudhry, Pakistan’s Relations with India, p. 41.

- Ibid., p. 41.

- Latif Ahmed Sherwani, ed, Pakistan Resolution to Pakistan, 1940-1947, Karachi, 1969, p. 235.

- Ibid., pp. 247-248.

- As cited in Saeeduddin Ahmad Dar, “Foreign Policy of Pakistan 1947-48,” in Ahmed Hasan Dani, ed., p. 363.

- 7 November 1947, Mountbatten’s Personal report as cited in Stanley Wolpert, Jinnah of Pakistan, New York, 1984, pp. 352-353.

- Abdul Samad Ghaus, The Fall of Afghanistan: An Insider’s Account, Washington, 1988, p. 67.

- Ibid., p. 68.

- Mahboob A Popatia, Pakistan’s Relations with the Soviet Union 1947-49; Constraints and Compulsions, Karachi, 1988, p. 27.

- Ibid., p. 70.

- Mohammad Ayub Khan, the first Muslim Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army (1951-1958) and later Pakistan’s president (1958-1969) recalled Pakistan’s defence capability at the time in the following words:

“Our army was badly equipped and terribly disorganized. It was almost immediately engaged in escorting the refugees who streamed by the million into Pakistan, and not long after that it was also involved in the fighting in the Kashmir. Throughout this period we have no properly organized units, no equipment, and hardly any ammunition. Our plight desperate. But from the moment Pakistan came into being I was certain of one thing Pakistan’s survival was vitally linked with the establishment of a well-trained, well-equipped, and well-led army. I was determined to create this type of military shield for my country”. See Mohammad Ayub Khan, Friends, Not Masters: A Political Autobiography, New York, 1967, pp. 20-21. - Popatia, p. 29.

- Ibid.

- M.S. Venkataramani, The American Role in Pakistan, 1947-1958, Lahore, 1984, pp. 15, 19-20.

Jinnah House in London

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Credit: fiction~dreamer

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Credit: fiction~dreamer

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Gandhi and Jinnah - a study in contrasts

An extract from the book that riled India's Bharatiya Janata Party and led to the expulsion of its author Jaswant Singh, one of the foun...

-

We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one State. ( Presidential Address to the Co...

-

Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creat...

-

Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the voice of one hundred million Muslims, fought for their religious, social and economic freedom. Through...