by P.H.L. Eggermont

Introduction

Introduction

In 1936 Pandit Nehru wrote in his Autobiography :

“The Muslim nation in India- a nation within a nation, and not even compact, but vague, spread out, indeterminate. Politically the idea is absurd. Economically it is fantastic; it is hardly worth considering….”

At the time not only Nehru and his followers but also the greater part of the Western authors, journalists, and political reporters were sceptic, or even opposite to the Pakistan-concept. However, in spite of all these ominous prediction Pakistan became a fact on the 14th August 1947, and, at present, nearly thirty years after, it is manifest that this state has energetically survived wars and calamities, has courageously resisted economic reverse, and has developed into an esteemed member of the United Nations.

Which mysterious forces may have caused the blind spot in the eyes of Nehru, and in the eyes of so many prominent Western intellectuals so that they failed to discern the strength of the Pakistan-concept?

The answer to that question lies hidden within a complexity of factors among which the most important one is the wide gap separating the Islamic and Hindu views regarding social, cultural and religious aspects of life.

As a matter of fact only the British have realized the unity of the sub-continent, and were able to guard it for over a century. In this respect Queen Victoria (1837-1904) was historically the first geographic Chakravartin. As, therefore, in the recent period the political unity of India happened to coincide with the traditional Hindu claim upon its ruling over the entire sub-continent, I am inclined to consider this mere coincidence to represent one among the factors which caused men like Nehru and Gandhi to close their eyes to the lesson of history teaching that partition and division had been the usual feature of the sub-continent for ages and ages.

Another mythical factor is the so-called “Absorption-theory”. In his book “Discovery of India” Nehru writes:-

“India’s peculiar feature is absorption, synthesis”. It is true, in antiquity this theory fitted in well with the facts: invaders like the Greeks in the 3rd century B.C., the Scythian in the 1st century B.C., the White Huns in the 5th century A.D., have been absorbed all of them.

The Muslims, however, are the exception to the rule. They have never been absorbed, though a great range of forms of peaceful co-existence can be noticed during the Muslim period.

How unacquainted the early Muslims were with the Indian culture is shown in the next lines written by Al-Beruni, the contemporary of Mahmud of Ghazni, who conquered the Punjab between A.D 1000 and 1026:-

“We believe in nothing in which they believe and vice-versa…. If ever a custom of theirs resembles one of ours, it has certainly just the opposite meaning”

Al-Beruni’s words seem to have remained valid until our days, for Mohammad Ali Jinnah, whose Centenary is celebrated at present, has explained during an interview in 1942 :-

“Islam is not merely a religious doctrine, but a realistic and practical code of conduct - in terms of everything important in life, of our history, our heroes, our art, our architecture, our music, our laws, our jurisprudence. In all these things our outlook is not only fundamentally different, but often radically antagonistic to the Hindus.”

In between Al-Beruni’s first notes on Indian creed and customs and the interview of Mohammad Ali Jinnah extends the gap of time filled by the autumn-time of the Indian Middle Ages, the preponderance of the Turco-Afghan states, the Empire of the Moghuls, and since A.D 1757 the power of the British Empire.

At first the British continued making use of the feudal structure of the Muslim and Hindu states they had conquered, ruling by means of the administrative Hindu middle class, and maintaining Persian as the language used in the courts of justice. The great change started only in the frame of the rise of liberalism and the big industries in England. Lord William Bentinck the first Governor-General of the entire sub-continent (A.D.1828-1835) replaced Persian by English, a reform of which he himself did not realize the importance, but which in the long run appear to have accelerated the modern development of the sub-continent a great deal. At first this reform was disadvantageous to the Muslims. The Hindus were quick to learn the new language, but they kept sticking to the use of charming Persian and useful Urdu so that they came to lag behind compared with the Hindus. Of 240 Indian pleaders admitted to the Calcutta bar between 1852 and 1868 only one was Muslim. The “Mutiny” of 1857 turned out to be disadvantageous to the Muslims as well. For a long time they were not permitted to follow a glorious career in the Indian army.

However, only thirty years later, in 1888, Lord Dufferin addressed the members the Mohammedan National League at Calcutta as follows:-

“In any event, be assured, Gentlemen, that I highly value those remarks of sympathy and approbation which you have been pleased to express in regard to the general administration of the country. Descended as you are from those who formerly occupied such a commanding position in India, you are exceptionally able to under-stand the responsibility attaching to those who rule.”

The scholar: Sir Syed Ahmad Khan

This Muslim renaissance, this recovery of Muslim political influence was almost entirely due to one Muslim whose indefatigable energy pointed his co-religionists the way to modern times. He was Sir Syed Ahmad (1817-1898). Starting his career as a clerk in the service of the East India Company in 1837 he finished as a member of the Governor General’s Legislative Council from 1878-1883. He had earned the confidence of the British by his saving many Europeans during the “Mutiny “, so that he was able to make the new rulers acquainted with the Muslim points of view they had been unaware of formerly. His activities comprised three fields, Islam, reconciliation with the British, and relation with the Hindus. As to Islam, after a visit to England in 1869 he became aware that Islamic theology should recover the dynamism it had possessed in the glorious past. In the same way as Islamic philosophy has amalgamated the scientific discoveries of the ancient Greek science during the middle Ages, it should react upon the new data provided by the recent Western science. There is no contradiction between the Word of Allah and the Work of Allah, he said. He spent much time to justify his effort by writing in two journals he had founded. His greatest contribution however was the establishment of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh where besides the study of Islam young Muslims could obtain English education. Many later political leaders as capable as the Hindus have studied there. Politically he preached firm loyalty to the British Crown so that he extricated the Muslims from their isolated position. His policy towards the Hindus was characterized by some distrust. When Lord Ripon created local self-government institutions he insisted that the Muslim communities should receive separate nomination.

This distrust sprang notably from anti-Islamic currents among the Hindus, as e.g. it appeared from the popular novel Anandamath written by the Bengali author Bankim Chandra Chartterjee in 1882. The contents of this novel represented an affront to good taste in general and an insult to the Muslim community in particular. These anti-Islamic currents were not universal at the time. At the first session of the Indian National Congress held in 1886 the President said:

“For long our fathers lived and we have lived as individuals only or as families, but henceforward I hope that we shall be living as a nation, united one and all to promote our welfare, and the welfare of our mother-country”.

Sir Syed however did not agree to that, and called the members of the Congress back to reality by saying in one of his speeches on the subject:-

“The proposals of the Congress are exceedingly inexpedient for a country which is inhabited by two different nations….Now suppose that all the English …were to leave India….then who would be rulers of India? Is it possible that under these circumstances two nations---the Mohammedan and Hindu—could sit on the same throne and remain equal in power? Most certainly not. It is necessary that one of them should conquer the other and thrust it down. To hope that both could remain equal is to desire the impossible and the inconceivable.”

In fact it is this antithesis between the idealistic Hindu One-Nation theory and the realistic Muslim Two-Nation theory which contained the seed of the separation realized more than 60 years later.

The Poet: Mohammad Iqbal

Sir Syed had rendered the Indian Muslims their prestige, but the 20th century needed someone who gave them a sense of separate destiny. The Hindus were so fortunate as to obtain at an early time, in 1918, a charismatic leader, Mahatma Gandhi. In their turn the Muslims acquired a gifted and inspiring poet. They had to wait until 1936 before a leader turned up who was acknowledged by all of them. The poet was Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938). As a student in Europe (1905-1907) he had discerned the portents of the approaching World-war I. He returned to India, filled with dislike for the selfish policy of the European national sates, but also with admiration for the active, and dynamic life of the Europeans themselves. During the war he published his vision on the relation between individual man, the world and God (1915 and 1918). Some people, he says, regard the development of the individual as supreme end, and the state as an instrument to that. Others exalt the state and regard it as far more important than the rights of the individual. Between these extremes Iqbal shows the middle way, viz. the development of the spiritual person in close connection with the communal group to which one belongs. Such an ideal society however, is only possible if it is based on Monotheism, Tawhid, for the idea of one God emphasises the essential unity of all mankind. The human society is one indivisible unit and man is related to man as brother, irrespective of colour, creed or race or geographical environment. Therefore he says:-

“That which leads to unison in a hundred individuals is but a secret from the secrets of Tawhid. Religion, wisdom and law are all the effects; power, strength and supremacy originate from it. Its influence exalts the slaves, and virtually creates a new species out of them. Within it fear and doubt depart, spirit of action revives, and the eye sees the very secret of the Universe.”

It is with a view to the creation of a Muslim Home-land meant to representing a spiritual centre in support of the other Muslims scattered over the remaining portion of the Indian sub-continent, that Iqbal said at the Session of the Muslim League in 1930 :-

“I would like to see the Punjab, North West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within the British Empire or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated North Western Indian Muslim state appear to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of North West India… The Muslim demand ..is actuated by a genuine desire for free development which is practically impossible under the type of unitary government contemplated by the nationalist Hindu politicians with a view to secure permanent communal dominance in the whole of India. Nor should the Hindus fear that the creation of autonomous Muslim states will mean the introduction of a kind of religious rule in such states. For India it means security and peace resulting from an internal balance of power, for Islam an opportunity to rid itself of the stamp that Arabian imperialism was forced to give it, to mobilize its law, its education, its culture, and to bring them into closer contact with its own original spirit and with the spirit of modern times.”

In 1933 a Muslim student at Cambridge, Chaudhari Rahmat Ali, proposed to give Iqbal’s project the name of Pakistan. The name struck the imagination of the masses, and was in general use as late as 1940.

The Leader: Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Iqbal was a poet, but no real politician. In fact the Muslims had at their disposal a qualified politician, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948), but he followed for a very long period the unitary point of view adhered to by Nehru and Gandhi until, at last , he was converted to the Pakistan concept in 1937. The reason may be sought for in his character on the one hand, and in the political situation on the other.

Jinnah was known as an incorruptible and very strict lawyer. A glimpse of his character appears perhaps from the next words he said in a speech held at Lucknow in 1937:-

“Think one hundred times before you take a decision, but once a decision is taken, stand by it as one man. “

When Muhammad Ali Jinnah started his political career, the Muslim League had got involved in the Khilafat Movement which dominated the political field from 1912 until 1924. In general the Indian Muslims tended to regard the Sultan of Turkey as the leader of the Islamic faith, though formerly, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan had said:

“You are the subjects of the British authority, and not those of Abdul Hamid.”

World-war I had turned the British Empire into the adversary of Turkey, and the harsh condition of its peace settlement had, for once, brought the Indian Muslims into line with Gandhi’s opposition against the British. It is why Mohammad Ali Jinnah as the then president of the Muslim League, and the National Congress signed the famous Lucknow Pact in 1916/1917. It was an agreement between the parties on the future Constitution of India according to which the Muslims were to have one third elective seats in the All Indian Legislature, and very reasonable percentages of the elective seats in the various provinces. In this respect one should realize that the strict and incorruptible lawyer Jinnah regarded the Lucknow Pact as a legal act, as a valid cheque on the future, and certainly not as a playing ball created by the political parties to play with of their own accord.

It is from the same point of view why he opposed Gandhi’s resolution of starting a peaceful non-co operation movement at the Nagpur session of the Indian National Congress in 1920. At the Conference there were 1050 Muslims among the 14582 delegates, but Muhammad Ali Jinnah was the only dissentient.

In a letter to Gandhi he wrote:-

“Your methods have already caused split and division in almost every institution that you have approached hitherto …people generally are desperate all over the country and your extreme programme has for the moment struck the imagination mostly of the inexperienced youth and the ignorant and the illiterate. All this means complete disorganization and chaos.”

The events of august 1921 proved how accurately Jinnah had judged the situation. The Islamic Moplahs of Malabar rose in revolt, murdered a few British administrative officers, finally turned against the Hindu landowners and money-lenders. Gandhi called off his peaceful non-co-operation movement, but preaching peace the had introduced the sword. Between 1920 and 1940 continued the series of the actions and counteractions between Muslims and Hindus which contemporaries like I myself used to read in the journals all over the world at the time.

Jinnah lost his influence in the National Congress, and, disgusted, he left India to establish himself as a lawyer in London between 1930-1940. There he was favoured by participation in the Round Table Conference of 1930-1931, where he met his famous co-religionist Muhammad Iqbal.

The result of this Round Table Conference was the 1935 Government of India Act, an impressive, but very intricate piece of work the most notable feature of which was the introduction of elections for 11 new Provincial Assemblies provided with their own responsible ministers.

In this connection Liaqat Ali Khan urged Jinnah to leave England in order to prepare the elections of 1937. Reminding his Muslim electorate of the Lucknow Pact 1916-17 he brought forward a moderate election programme. However, as the Muslim League was still a middle-class organization without a firm grip on the masses the elections became a brilliant success of the Congress party, which won the majority in 5 Provinces, and turned out to become the largest party in 2 others. Without any regard to Jinnah’s co-operation programme Nehru formed Congress ministries in the Hindu-Majority provinces where the Muslim League had captured a substantial number of the Muslim seats. In Uttar Pradesh the Congress went even so far as to propose that Leaguers would be taken into the Cabinet only if the League dissolved its parliamentary organization and if all its representatives became members of the Congress. This was what later on Sir Percival Griffiths called “a serious tactical blunder of Nehru”. It was even worse than that. Jinnah regarded it as treason to the Lucknow Pact, and he declared:-

“On the very threshold of what little power and responsibility is given, the Majority community have shown their hand, that Hinduism is for the Hindus. Only the Congress masquerades under the names of nationalism.”

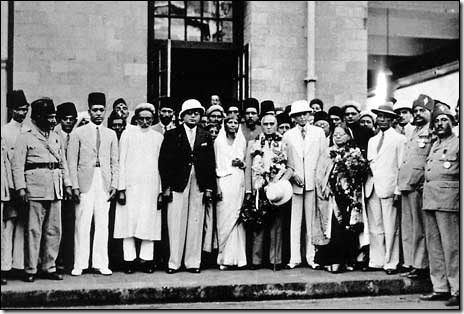

On Iqbal’s advice Jinnah started to turn the League into a party of the masses. He reduced the annual membership to two annas. In the same way as Nehru and Gandhi he travelled all over the country conducting a fiery campaign. The number of his followers rose quickly and between 1938 and 1942 the League won 46 out of 56 by-elections in the Muslim constituencies throughout the provinces. He became the Quaid-i-Azam, the Great Leader, and against the Congress’s point of view that only the Congress represented the people of All-India, he was now able to put his counter-claim that the League, and only the League, could represent the Indian Muslims.

On 23rd March 1940 he took the final step leading to autonomy and separation. At the annual session of the League at Lahore the next resolution was accepted:-

“No constitutional plan would be workable in this country or acceptable to the Muslims unless it is designed on the following basic principles, viz. that geographically contiguous units are demarcated into regions which should be so constituted with such territorial adjustments as may be necessary, that the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in a majority, as in the north-western and eastern zones of India, should be grouped to constitute Independent States in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign.”

The political correspondents of the press were quick to grasp the significance of this intricate long phrase, and they called it the “Pakistan resolution.”

When the long valley of World-War II was passed the political strife, or better the civil war, between Hindus and Muslims exploded, together with its horrible consequences. It ended in the replacement of Lord Wavell by Lord Mountbatten, the shock therapy by Mr. Attlee, who established the month of June 1947, and later on the 15th of August 1947 as the date of the transfer of power. It ended in the dramatic migration of 14,000,000 people, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs as well, perhaps the most massive simultaneous migration known in the history of the world. On 7th of August Jinnah flew to his native town Karachi. He was 71 years of age by now. On 11th of August he opened in his capacity of Governor General the first session of the Constituent Assembly of the recently created autonomous and independent State of Pakistan, and spoke:-

“You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any place of worship in the State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion, or caste or creed that has nothing to do with the fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of our State…Now, I think we should keep that in front of us and as ideal…”

P.H.L. Eggermont is the Professor at the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium.

Source: World Scholars on Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Edited by: Ahmad Hasan Dani, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 1979.