|

| Click on the image to enlarge |

A Pakistani View

by S.M. Ikram

Jinnah was not invited to the later sessions of the Round Table Conference, but he was now residing in England, and had opportunities of meeting the delegates from India. An important contact, which he effectively renewed during this period was with Sir Muhammad Iqbal, who had come as a delegate to the Round Table Conference. Jinnah was the principal speaker at a reception given in honour of the poet by Iqbal Literary Association and thereafter invited him to lunch at his house. Thus began a series of meetings which were to leave a mark on the course of India’s history. Jinnah was not now a delegate to the Round Table Conference, but during the first session, which he attended, he had criticised to conception of the central federation, which other delegates had supported enthusiastically. His objections were partly from the nationalist anglet (sic) – the inclusion of the autocratic princes at the centre would “water down democracy” – and partly from the Muslim point of view – a strong centre would nullify the provincial autonomy which the Muslims valued so much. Iqbal, on the other hand, had a few years before, held out his plan for a Muslim bloc in the North-West. This did not receive much consideration at the Round Table Conference, but the separation of Sind, and grant of full reforms to the North-West Frontier Province were bound to pave the way for its fulfillment. This plan, the poet discussed at length with Jinnah, and gradually convinced him that in this lay the only hope for a contented, peaceful India in general and for the bulk of Indian Muslims in particular.

Meanwhile he was getting reports from India that Indian Muslims were a flock of sheep without a shepherd. The Aga Khan’s leadership was ineffective, as he wanted the palm without the dust, and could not give up the health resorts of France and Switzerland. Maulana Muhammad Ali was dead. So was Sir Muhammad Shafi, and even if he had been alive, he was too closely associated with a pro-British policy to inspire general enthusiasm. The League and the Muslim Conference had become the plaything of petty leaders who would not resign office, even after a vote of no-confidence! And, of course, they had no organization in the provinces, and no influence with the masses.

It was in these circumstances that certain well-wishers of the Muslims turned towards Jinnah. They requested him to return to India, and once again lead to army, which was first becoming a rabble. Iqbal joined in these appeals. Jinnah relented, but even now he would only visit India for a few months and return to England again. In 1934, however, he was elected the permanent president of the All-India Muslim League, and finally returned to India in October, 1935.

Back in India, Jinnah began to reorganize the All-India Muslim League. Its annual session was held at Bombay in April 1936, under the presidentship of Sir Wazir Hasan, and its constitution was revised to make it more democratic and living organization. Steps were also taken, for the first time, to set up a machinery for contesting elections on behalf of the Muslim League. A central election board with provincial elections under the Government of India Act of 1935. Jinnah toured the country to convass (sic) support for the League candidates, but his efforts were only partially successful. In the Punjab, he had the constant support of Iqbal, but could not come to an agreement with Sir Fazl-i-Hussain, the Unionist leader and League fared very badly in that ‘key’ province. Experience in Bengal was similar. In the elections, the League was actively assisted by the Jamiat-ul-Ulama, and had generally the goodwill of the Congress, which had been receiving support for Jinnah’s Independent Party in the Central legislative Assembly, but it failed to make much headway against firmly entrenched provincial parities.

The Rallying-Post

The provincial elections of 1937 produced many surprises. The League had not come out with flying colours. The Congress, on the other hand, achieved a success, which neither its supporters nor its opponents had anticipated. Most provincial Governors and British officials expected at the provincial election a repetition of the previous elections to the Central Legislature, when Congress had won about 50 per cent of the Hindu seats. They looked to the provincial parites, which they had encouraged in various areas – the Unionists in Punjab, the Justice Party in Madras, the Zamindars in the Nationalist Party in U.P., the Marathas in Bombay – and were sure that although the Congress may be the largest single party, it would have to depend on others to form ministries. Here they were to be completely disillusioned. The organizing ability of Sardar Vallabhbhi Patel, who had succeeded Dr. Ansari as the Chairman of the Parliamentary Board, the army of the workers, which the Congress had built up during the previous twenty years, the magic name of Mahatma, and the whirlwind tours of the president, Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru, completely upset the official calculations. The Congress triumphed in all the Hindu provinces and even in the North-West Frontier!

There is no doubt that this unexpected success went to the head of the Congress leaders. Before and even during the elections, they were friendly to the Muslim League. Now they were cold and distant. Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru declared at Calcutta that there were only two parties in the country – the British and the Congress. The League had fared so badly at the elections that it was not necessary to acknowledge its existence. To this attitude of high disdain, two other factors contributed. The Congress president was surrounded by certain left wing – almost de-Muslimised – Muslims, who later left even the Congress fold for the Communists’ ranks. They urged on Nehru, that it was “medieval” to recognize political parties based on religions, and the Congress had only to organize a vigorous Muslim Mass Contact Movement to achieve the same success amongst the Muslims, which it had gained among the Hindus. Nehru was carried away by these visions, and an open breach occurred between the Congress and the League. While in the original elections, the Congress had supported the League in U.P. now it set up a candidate to oppose the Muslim League in Bhraich constituency of U.P. which had returned a Leaguer, who died shortly after the elections.

The personality of the chairman of the Congress parliamentary board was another factor, which drove the Congress away from the League. Sardar Patel was a great organizer but for a man of his ability and importance, he was amazingly ill-informed about the background of Muslim politics, and even otherwise perhaps freedom from communalism was not one of his many gifts. He was at this time at the summit of the Congress parliamentary board, bossed over all government in the Congress provinces. He had to decide the question of Muslim representation in provincial government, and he dealt with the problem in his usual firm and unimaginative way. If he had faced the question in a spirit of statesmanship, he could have seen that Sir Sikandar Hayat and other Muslim premiers had already tackled the corresponding Hindu problem in the Muslim provinces, in a manner which could be a very safe guide to the Congress. Sir Sikandar Hayat’s party was in absolute majority in the Punjab Assembly, but he offered the Hindu seat in the Government to the Hindu Mahasabha, and although Raja Narendara Nath, the president of the Hindu Party, was unable to accept it owing to old age, his nominee, Sir Manohar Lal was appointed a minister. There was really no other way to give honest, real, representation to the minorities. If a minister had to be taken not on account of affiliation to the party, or any other personal claim, but to represent the minorities, it was obvious that he should be their genuine representative and not a stooge of the party in power. This the iron-willed Sardar would not – or could not – grasp. Under the constitution, representation had to be given to the minorities. So he was prepared to have Muslim ministers even from the Muslim League – but then, they must resign from the League, sign the Congress pledge, and abide by its discipline. In other words, the minority representatives were not to represent the minorities but the Congress! In imposing his iron discipline, the Sardar had some initial difficulties. The Muslim League had not done well in predominantly Muslim areas, but it had won the vast majority of seats in the Congress provinces. In some of these – like Bombay – not a single Muslim had been returned on the Congress ticket. So what was to be done about the representation of the Muslims in the Governments of these provinces? The problem was somewhat complicated but the efficient, resourceful Sardar was not going to be baffled by these difficulties. He offered the ministry to any Tom, Dick or Harry amongst the Muslim members who was prepared to sign the Congress pledge and so the farce of Muslim representation was complete.

The procedure adopted was, of course, a negation of the constitutional safeguards for the Muslims, but it was also less than fair to the Muslim League. Before the elections the Congress and Jinnah’s Independent Party had closely collaborated with each other in the Central Legislative Assembly and many Congress resolutions against the Government succeeded only on account of Jinnah’s support. Their relations during the elections were also friendly. Later, when after the elections in 1937, the Congress at first refused to accept office, and the Governors called the League leaders, as representing the next largest party, to form what we called interim Ministries Jinnah would not allow this. It is known that in some cases, the leaders of the League parties in the provincial legislatures e.g. Sir Ali Mohammad Khan Dehlavi in Bombay were quite willing – even keen – to become premiers but Jinnah overruled them. He would not profit by the Congress refusal to come in, or do anything, which might jeopardise the prospects of an effective League-Congress collaboration on which his heart was set.

The Congress party leaders, however, when it was their turn to be invited by the Governors, completely ignored the Muslim League. This must have hurt Jinnah; what followed was calculated to rouse his ire still further. The Congress Government had taken one false step in taking, as Muslim Ministers, persons who did not command the confidence of the Muslims in the legislature. This false step was succeeded by many more of the same type. In the absence of a true Muslim representative in the Cabinet, the congress Government had nobody to advise them about the views of the Muslims, when they took decision affecting the general population. The so-called “Muslim Minister” knew very well that he was governed by the Congress pledge, and the iron discipline of that party. He usually represented himself alone, and lacked that moral courage which comes from having “big battalions at one’s back.” In many cases, he was just a newcomer to the Congress ranks, avowedly for the sake of the office – and did not carry with his colleague in the Cabinet, anything of the influence which a Syed Mahmud or Yaqub Hassan would carry. Bereft of any following, and any mission, that he was to watch the Muslim interests – and in many cases, even the support of a contented conscience – the Muslim Minister was a pathetic figure, and deprived of his frank advice, the Congress Governments took several steps, which caused deep resentment amongst the Muslims – as well as by Hindu untouchables – and a committee has reported on the hardships, to which Muslims were exposed under the Congress rule.

The second half of the year 1937 was one of the darkest periods through which Indian Muslims have had to pass since 1857. Their central political organization had failed to show any effectiveness at the polls. Over the greater part of the country, where the Congress ministries held sway, they felt that the Hindu Raj had come. They suddenly realized that all the fears, which Sir Syed and Viqar-ul-Mulk had expressed about their future, were coming true. They were most disheartened and sore at heart. They saw no way out of their predicament, and thought that soon the Congress, with its vast organization, and the policy of corrupting a few ambitious, un-principled Muslims, would extend its sway over the Muslim majority provinces and the while country would be come a vast prison-house for them.

The prospects for the Muslims were most gloomy and many faint hearts began to suggest that they should settle with the Congress on its own terms. There was however one light which burned bright and clear. Jinnah has been called a proud and haughty person, and this trait of character may have caused him as his people occasional difficulties. This was, however, the time when just these qualities were needed. In the midst of the storm he stood like a rock. He was the proud representative of a proud people and he hurled defiance at the pretensions and the dreams of the Congress. He was not going to lower his flag to come to terms with the Congress. Far from his accepting conditions while being offered seats in the Congress Governments, it would be he, who would impose conditions!

Indian Muslims are not likely to forget the resolve stand which Jinnah, without any visible following, without much support in the legislatures, and inspired solely by his sense of duty and his faith in his people, took at this juncture. But there was another great Muslim who, although in the background, gave Jinnah powerful and effective moral support. Jinnah had written about Iqbal.

“To me he was a friend, guide and philosopher, and during the darkest moments through which the Muslim League had to go, he stood like a rock and never flinched one single moment.”

Gradually the darkness began to lift. The Muslims saw the light and rallied round. Those in the Muslim majority provinces saw what was happening to their co-religionists in the Congress provinces and were deeply touched. They now realised that except through a powerful, All-India organization they had no means of saving themselves. So after having decisively defeated the League in the elections, the Muslim premiers of the Punjab, Bengal and Sind, came to terms with Jinnah and agreed to abide by the policy and decisions of All-India Muslim League in all-India matters.

Search For Security

The significance of the Lucknow session of the League was not on the Congress leaders. They realize that their treatment of the Muslims in the Congress provinces had been taken as a challenge by the entire Muslim India, which was prepared to meet it. The firm, disciplinarian policy of the iron dictator – the Sardar – had given results, quite different from what he expected. Thinking Hindus began to criticize the want of statesmanship shown by the Congress leadership in dealing with the Muslims. Tairsee, president of Hindu Gymkhana of Bombay, criticised, in the columns of Bombay Chronicle, the unstatesmanlike attitude which the Congress leadership had shown in refusing genuine representation to the Muslims in Congress Cabinets. Sardar Sardhul Singh Caveeshar of the Punjab expressed the same view in a long letter to Mahatma Gandhi. Sir Chiman Lal Sitalved criticised the unhappy development in the presidential address delivered in December 1937 at Calcutta session of All-India Liberal Federation and contrasted the unwise rigidity shown by the Congress leaders with the statesmanship displayed by the Muslim premier like Sir Sikandar Hayat.

The Congress leaders realized that they had blundered and appeared willing to take Muslim representatives in the Congress Cabinet on less exacting terms. Now it was Jinnah’s turn to be firm and unbending. The numerous unity talks which started between him and the Congress leaders, usually broke down on the question of the representative character of the Muslim League. His plea was that in 1916, when alone there was an agreement between Hindus and Muslims, the League had been taken as the sole and the authoritative representative of the Muslims and the Congress should now acknowledge its position in the same way. This, the Congress considered incompatible with its claim of speaking on behalf of entire India, and the negotiations broke down. Perhaps the truth in that what had happened in 1937, had not only embittered Jinnah but had finally convinced him that there was no safety for the Muslims in the goodwill of the Congress or the Hindus.

S.M. Ikram was a member of the Indian civil service and after partition held a number of important positions in the civil service of Pakistan. He has also published books in both Urdu and English on a variety of topics related to the history and culture of the Muslims of the subcontinent. In the excerpt quoted above, taken from a series of biographical sketches of Indian Muslim leaders, he discusses of the re-organization of the Muslim League in the thirties under the leadership of Jinnah.

Source: Muhammad Ali Jinnah Makers of Modern Pakistan. Edited by: Sheila McDonough (Sir George Williams University) D.C. Health and Company, Lexington, Massachusetts, USA.

Quaid-e-Azam's Visit to Peshawar in 1936

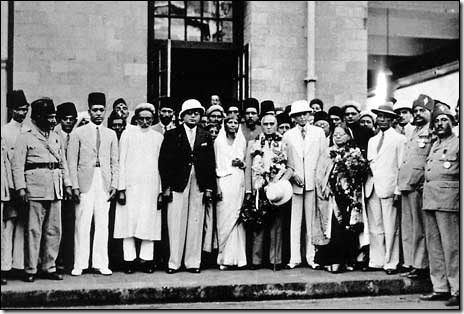

The Historic Group Photograph of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah at his Last Visit to Islamia College, Peshawar, N-WFP, Pakistan (12.04.1948 CE) (Courtesy of Prof. Dr. Taskeen Ahmad Khan, Associate Dean, Associate Faculty of Urology, Khyber Medical University, Peshawar (nb: From the Personal Library File of Maj. Gen (Retd.) Anwar Sher Khan, Peshawar).

by Mohammad Anwar Khan

The Government of India Act 1935, though considered “fundamentally bad”1 by the Muslim leaders, was a significant step, as the future constitutional framework of India was based upon it. Elections to the provincial assemblies were announced for the fall 1936-37 and the Muslim League in the 24th session, in Bombay, on the 12th of April 1936, resolved to contest the provincial assemblies elections and authorised the Quaid to organise elections boards at the central and the provincial level and also devise “ways and means” for contesting the forthcoming election.2 The Quaid, accordingly, invited a large number of influential Muslim leaders all over India for a meeting by the end of April 1936 at Delhi and also went to Lahore for consultation with the leaders of Punjab. He addressed letters for this meeting to a large number of the Muslim leaders from the NWFP, notable amongst them were Pir Bakhsh,3 Malik Khuda Bakhsh.4 No one from the Frontier attended this meeting. Pir Bakhsh did not acknowledge it. The Quaid met later Malik Khuda Bakhsh and Rahim Bakhsh Ghaznavi at Lahore at the residence of Mian Abdul Aziz.5

The Frontier was given representation in the Central Parliamentary Board. Pir Bakhsh, Malik Khuda Bakhsh, Allah Bakhsh Yousufi and Abdul Rahim (Rahim Bakhsh) Ghaznavi were appointed as members of the board from the Frontier. The Quaid was very keen at this time to learn more about the Frontier. It was a Muslim majority area. He had also fought for its provincial status. His knowledge of the Frontier was not upto date: this is discernible from his correspondence with Pir Bakhsh6 on September 13, 1936 and that with Abdul Ghafoor, Allah Bakhsh Yousufi and few others.7 He wanted to know more as he intended visiting Peshawar.8 The Quaid for the most part depended upon Pir Bakhsh with whom he had developed acquaintance since 1931.9 None would tell him the details. Malik Khuda Bakhsh rather has asked him in April to visit Peshawar10 and to see things for himself. In October he decided to tour Punjab and Frontier, and he accordingly wrote to the Frontier leaders including Sahibzada Abdul-Qayum11 whom he knew as member of the Imperial Legislative Council a dna colleague at the Round Table Conference, supporting the cause of Indian Musalmans in general and that of Frontier in particular. Sahibzada being attached to government agency, asked one of his Lieutenant Agha Lal Badshah, who had worked under him in the British Political service in Waziristan to extend a formal invitation to the Quaid on behalf of the Muslims of the NWFP.12 He also asked Pir Bakhsh to assist Lal Badshah in which a number of Muslim Peshawari leaders participated, a resolution was drafted requesting the Quaid to visit Peshawar. It was written by Pir Bakhsh and Sufi Abdul Aziz Khushbash “an energetic national worker of Peshawar city” as Pir Bakhsh introduced him in his letter to the Quaid, was deputed to deliver this invitation to the Quaid at Lahore.13

Abdul Aziz Khushbash,14 in his interview with the author stated that his travel expenses were borne by Syed Lal Badshah. The Quaid was staying at the Faletti’s Hotel. A room was provided for him too. He stayed for two days at Lahore and then accompanied him to Peshawar by evening Bombay mail. He sent telegram on the 17th of October 1936 prior to their departure to Syed Lal Badshsh intimating the time and day of their arrival in Peshawar. Both reached Peshawar next morning. Nawab Mamdot, saw the Quaid off at the Lahore railway station.15

The Quaid arrived in Peshawar on Sunday, the 18th of October 1936.16 Bombay express reached the City station at about 8 AM. About 400 persons welcomed him at the station.17 Secret police report tells us presence of prominent persons amongst them like Sahibzada Qayum, Ghulam Samdani, Pir Bakhsh, Lal Badshsh, Chan Badshah, Mohammad Usman Naswari, Rahim Bakhsh, Ataullah and Abdul Hye.18 It also records presence of about thirty Khaksars and 78 boyscouts. The Quaid was greeted and garlanded.19 He shook hands with all those in the front.20 He was dressed meticulously western, wearing top hat, long coat, beneath it a well cut suit with English shoes, took aback many credulous Peshawaris, dubbed by one as an Englishman.21 The Quaid was taken in procession, in a convertible grey car provided by Sahibzada Qayum. The station receptionists were later joined by the public, and the procession including volunteers, a Rover’s batch of Islamia College,22 students from Edwardes’ College, left for the city through a pre-planned route. The Quaid was driven slowly, seated by him were Pir Bakhsh, Lal Badshah in the back seat and perhaps Hakim Jalil in the front seat as gleaned through a photograph taken on the occasion. The procession entered the city through Hashtnagri, Karimpura bazaar, to the Ghanta Ghar, then through Chowk Yadgar, the party proceeded via Phurgaran towards Yakatut and terminated at the residence of Sahibzada Qayum, which had been furnished for the Quaid’s stay.23 Mr. Ayub Khattak then a second year student of Islamia College and incharge Rover’s group recollects that flowers were showered at the procession from a balakhana near Ghanta Ghar, and a handful of sweet (shakarpara) was pelted over the motorcar from the Sufi sweet house (still situated in Ghantaghar at the entrance to Karimpura) one ball hitting the Quaid at the right eyebrow, which gave reddish look for a quite a while. It all took about two hours to reach Mundiberi. Here the Quaid thanked all, especially the student community and promised to meet them later during his stay at Peshawar.24

The Quaid stayed for a week from 18th of October to the 24th at the Mundiberi residence of Sahibzada Qayum.

The first day in Peshawar was spent quietly. There is no day record maintained by one, of this event. The news media was not much alive to it. The Khyber Mail, then a weekly, has only given a three line account of the arrival and a column on the departure. The Frontier Advocate and the Sarhadi Samachar both Hindu papers, on which I could not lay hand, are reported not to pay much heed to the visit. Al-Jamiat’s file for 1936 is not maintained and also those of Islahe Sarhad are not traceable. The story therefore is based on a few secret police reports and recollections of men connected with this event. Some exaggerated versions of this visit have lately appeared.

The Quaid was visiting at this time in his individual capacity. The public was least conscious of his mission less to talk of the Muslim League. An educated frontierman had heard about him as supporter of the Frontier cause in the Legislative Council and at the Round Table Conference. His Fourteen Points, which inter alia had urged for reforms in the Frontier, has aroused liking for him. His struggle for the Muslim cause, was penetrating the Frontier though slow, but steadily. The students of Islamia College invited him in May 1936 to preside over the Prophet’s day function.25 This he could not attend, but he sent message26 for the occasion. The Khyber Mail in its weekly political and educational columns was portraying both literary and political efforts of the Indian Muslim leaders and the Quaid and Iqbal found place in them. The Frontier politics had been completely overshadowed by the Khudai Khidmatgar (redshirt) movement, which had affiliated itself with the Indian National Congress. It was a movement that had deep roots in the rural areas and its leader, Abdul Ghaffar Khan, had emerged as a socio-political saviour and his arrest had caused political restlessness in the area.27 Coinciding it the approaching provincial elections had produced hectic political life. Redshirt election campaign offices were opened all over the province. District parliamentary boards, were set up during the middle of 1936. Meetings were organised and the public made conscious of their rights. Dr. Khan, Abdul Qayum Khan, Qasim Shah Mian, Ghulam Rabbani, Ghulam Mohammad Lundkhwar, Mehar Chand Khanna, Dr. C.C. Ghosh, Ashiq Bad Shah, Mian Samin Jan, Kamdar Khan and others were daily reported addressing meetings in the length and breadth of the province. The government had to resort to arrests in certain cases, which further made their cause popular. August 21, was observed as Ghaffar Khan Day all over the province.28 The Socialist Party of Peshawar joined hands with the Redshirt.29 There were, in fact, only two parties in the Frontier, the government and the Redshirt, as claimed by the Congress leadership. The others were all disarrayed. Non-Congressite Muslims would hold inconclusive periodic meetings, and one like it was held on August 25-26th at Abbottabad to prepare the election manifesto and devise means for the forthcoming elections,30 but personal rivalry marred unanimous stand. The Muslim Azad Party, was split up into Nishtar and Pir Bakhsh group. Khaksars and Ahrars were mostly ineffective.

The political situations, therefore in October 1936, in the Frontier province was quite blurred. The Quaid was to analyse it properly. He, therefore, in the first instance met the Redshirt leaders, at about 6 p.m. on the first day of his arrival. The secret police reports Ghulam Mohammad Lundkhwar, Abdul Qayyum Khan, Qaim Shah Mian and Dr. C.C. Ghosh, calling on the Quaid on that evening. They discussed the affairs in general with him.31 The visitors formed part of the city parliamentary board. The Quaid persuaded them to wind up this board. To this they did not agree.32 He asked Qayyum Khan according to the secret police, report, to join the Muslim League. Qayyum later reported to Dr. Khan that he refused it.33

Next day, that is the 19th of October, the Quaid addressed the students of Edwardes College during the forenoon hours. There is no authentic information on this visit. The police secret reports mention of a gathering of about 200 students in College hall, in which, the Quaid explained the object of his visit to Peshawar. He appreciated political awakening in the Frontier and hoped that it would play an important role in the future constitution of the country.34

The same evening at about 4 p.m. the Quaid addressed the public of Peshawar at Shahibagh under the auspices of Muslim Azad Party. The news for this meeting had been customarily heralded in the city. Agha Lal Badshah presided over the meeting and Pir Bakhsh acted as the stage secretary. Sources vary on the number of audience.35 Police report indicates presence of about one thousand persons. Khushbash puts this number to 4000. Malik Shad estimates between two thousand to two and a half thousand (Professor) Jalalud Din Khilji, (ex-Principal Islamia College) then a Youngman of about 25, who happens to have reached the meeting spot unscheduled, found a small gathering not exceeding 300 persons. All accounts confirms that a good number of Hindus, mostly lawyers and the Sikhs were also present. The Quaid was as usual wearing western dress, a sola hat, was noticed smoking cigar on the dais. Many took him for an Englishman36 and quite a few left when he addressed them in English as it was not followed by all.37 The special branch timed the speech about 30 minutes, explaining to all that he had not come to lend support to any particular political group in the province, but to enlighten them on the aims and objects of the All India Muslim League. He also talked for a while on the 1935 Act and exhorted the Muslims to forge unity in their ranks and files, evolving one united party “Should they form such a party Hindus will follow suit”. He emphasized that the Muslim League aimed at producing liberal and progressive minded nationalist who could lead their nation to freedom.38 He advised them to send their best men to the assembly.39 He also asked the Hindus and Sikhs to sent their best too so that Hindu-Muslim unity is cemented and way paved for swaraj.40

Pir Bakhsh at the end of the speech gave a resume of it in Urdu. The meeting dispersed by about 5:30 p.m.41

On Tuesday, the 20th of October, the Quaid visited Islamia College on the invitation of the Khyber Union, the student organisation. The chief informants for this function are Ayub Khattak, Abdul Manan,42 both second year students of Islamia College. Malik Shad also participated in this function and has some dim recollections of it. Ayub Khattak informs that the college administration was not happy with this invitation and the organizers had to assure the Principal that the guest would not make any political speech. Khatak, Manan, and few others who were interviewed confirmed that Sahibzada Qayum was not present in the function.43

The Quaid was welcomed on entering the hall (Roosekepple) by students who had occupied it to full. The Principal (R.H. Holdsworth) welcomed the guest, as president of the Union. Prof. Mohammad Shafi, in his address paid tributes to the Quaid for his efforts in bringing unity in Muslim thought. He dwelt at length on the concept of Muslim unity and quoted extensively from Iqbal. The Quaid spoke for about half an hour. He advised the students “to advance themselves politically and educationally”.44 He was sure that this seat of learning (Islamia College) will one day equal the glamour of Al-Azhar and Cordova.45 Mohammad Yusuf Khalil, the vice-president of the Union, thereafter dilated on the objectives of the student body touching also upon the Pathan code of honour and ethic and requested the guest to become their honorary life member. The membership register thereafter was presented to him. The Quaid while singing it remarked that it is so endearing to his heart that he was signing the document without reading it.

This function, in all probability, took place in the afternoon.46 The meeting soon after adjourned with no tea party.47

There are positive evidence that the Quaid’s visit to Landi-Kotal was on the 21st or the 22nd. A group photograph at Landikotal in currency for a while in Peshawar was lately displayed at the centenary exhibition at the University of Peshawar. Malik Saida Khan Shinwari played host for him at his village in Landi Kotal. No positive date for this visit could be ascertained. It certainly was not Friday, the 23rd of October, as Malik Shad affirms that the Quaid performed Juma prayer in Masjib Mohbat Khan, wearing fez, under the imamat of Hafiz Noor Mohammad.48 The government record at the political Agent Khyber office is not in order to establish the correct day of visit.

The Quaid’s stay from 21st to 24th is also shrouded in myth. No definite story can be built as there is no authentic record with the exception of a secret police report that the Quaid met important Muslim leaders on the 23rd at the residence of Sahibzada Qayum, in the cantonment area in which Kuli Khan, Abdul Rahim Kundi, Pir Bakhsh, Abdul Rahman, Lal Badshah and Hakim Abdul Jalil participated.49 There is no detailed account of the meeting. The report concludes that a branch of the provincial Muslim League was formed on the suggestions of the Quaid with Khuda Bakhsh as president, Pir Bakhsh secretary and Hakim Jalil, Rahim Bakhsh, Abdul Latif, Syed Ali and Lal Badshah as members of the executive committee.50 Another report emanating from the same source reveals that Abdul Wadood Sarhadi alongwith a few other met the Quaid on the 24th and apprised him of the situation in the province. Wadood did not show any inclination to join Muslim League, on the contrary he forecasted that the Khudai Khidmatgar will win the forthcoming election and the Muslim League stood no chance to compete with them.51

This was the plea also taken by all other political leaders. There are indications that the Frontier leaders were not keen then to bet on the Muslim League for the forthcoming provincial elections and therefore they all preferred to contest the election in their individual capacity rather than as League candidates. The Khyber Mail carried the following column by its staff reporter on the conclusion of the Quaid’s tour of the Frontier.

“Mr. Jinnah saw works of all shades of opinion and had an exchange of views with them. A number of representative Muslims from all over the Province met him on Friday afternoon.

After a long discussion it was decided to form a party in order to take steps for the early formation of a Provincial Muslim League in the NWFP. Members of this Consultative Board include about 20 members of the Independent Party of the Province with Mr. Pir Bakhsh Khan MLC as convener.

It is proposed to hold a representative meeting of the Frontier Muslims of all shades of political thought in the first week of November at Peshawar in order to finally decide the question of the formation of the Muslim League. This decision has excited considerable interest in political circle of the Frontier. The majority of the workers in Peshawar seem to agree with Mr. Jinnah as regards programme of the League which they are studying keenly at present.

Mr. Jinnah before his departure told the Press that he was entirely satisfied with the result of his Frontier visit and cherished strong hopes of a bright future.

Members of the Independent Party, who owing to their election activities could not attend the above meeting have telegraphically informed of the above result. Mr. Jinnah has promised to visit the Frontier again whenever it is necessary for him to do so in the interest of the new Board. It is also stated that Maulana Ahmad Saeed, Secretary of Jamiatul Ullama-e-Hind, Delhi, will be deputed by Mr. Jinnah to do propaganda in the NWFP on behalf of the Muslim League.”52

The Quaid left Peshawar on the 24th evening. He was seen off at the railway station by about fifty persons important amongst them Pir Bakhsh, Lal Badshsh and Abdul Jalil.53

Mohammad Anwar Khan is Director, Institute of Central Asian Studies, University of Peshawar.

References

- Jamilul Din Ahmad, Historic Documents on the Muslim Freedom Movement p. 193. Hereafter cited as Historic Document.

- Ibid.

- The letter to Pir Bakhsh presently form part of Aziz Javed collection.

- Khuda Bakhsh to Jinnah DIK 30-4-1936 QA Paper cell Islamabad.

- This information is based on the statement of Mr. Ghaznavi.

- Aziz Javed collection.

- Abstract of NWFP, Police Intelligence Secret File No. 94 P. 319.

- Ibid.

- “The role of NWFP in Pakistan Movement” by Pir Bakhsh in Dawn Supplement May 12, 1975.

- Letter.

- The information from Malik Mohammad Shah and Rahim Bakhsh Ghaznavi.

- Ibid.

- Pir Bakhsh to Jinnah, Peshwar 14-10-1936. QA Paper Cell.

- The title of Khushbash (happy going) was conferred on him by Pandit Amir Chand Bambwal, the editor of Frontier Advocate in prison during 1922 on account of his jolly disposition.

- Mr. Rahim Bakhsh Ghaznavi, a follower of Nishtar, informs that Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar, then an opponent of Pir Bakhsh was highly alarmed on hearing the Quaid’s visit on the invitation of the rival group. He sent the two brothers, Allah Bakhsh Yousufi and Rahim Bakhsh Ghaznavi to Lahore to apprise the Quaid of their standpoint and to ask him not to do anything which in any degree harm their group position. Later Nishtar went in advance to see him at the Noshera railway station and tried to convince him of his viewpoint. It seems to have made little effect on him because later developments show that the Quaid could not under any circumstance encourage schism amongst the Musalmans.

- Khyber Mail, Oct. 18, 1936 p. I Col. 2.

- Abstract of Intelligence p. 369.

- Ibid.

- Khyber Mail.

- Malik Shad.

- Malik Shad says that Mian Mohammad nicknamed Nim Shah said so.

- Mr. Ayub Khattak accompanied the group to the Station and then joined the procession upto the residence.

- Ayub Khattak’s interview. This statement is also corroborated by Malik Shad.

- Malik Shad deposes that Pahlavan Faqir Mohammad and Fazal Mahmood were reciting Iqbal’s poem in the front line.

- Khyber Mail May 10, 1936 P. I Col. 2.

- Ibid., June 14, 1936 P. 2 Col. 4.

- Khyber Mail. There are many entries to this effect In 1936 file.

- Khyber Mail August 16, 1936, p. I Col. I.

- Ibid., October 4, 1936 p. I Col. 2.

- Ibid., August 16, 1936 p. I Col. I.

- Abstract of Intelligence op. cit., p. 369.

- Ibid.

- Abstract of Intelligence o.p. cit., P. 377.

- Ibid., P. 381.

- Ibid., P. 381.

- Professor J.D. Khiliji recollections.

- Ibid.

- Abstract of Intelligence op. cit., p. 382.

- Khyber Mail 25th Oct. 1936 p. I Cols. 2-3.

- Abstract of Intelligence op. cit.

- Malik Shad.

- Mr. Abdul Manan Khan is currently Agriculture Secretary to the Government of NWFP.

- Dr. Sakhaullah ex-Professor of Arabic also lends support to it.

- Ayub Khattak’s recollections.

- Abdul Manan’s recollections.

- Ayub Khattak asserts that it was in the afternoon. Abdul Manan would not remember it. Dr. Sakhaullah thinks it was in the forenoon. The College’s own account is silent about it.

- Ibid.

- He is not quite sure, but thinks it was Hafiz Noor.

- Abstract of Intelligence op. cit., P. 382.

- Abstract of Intelligence op. cit., P. 382.

- Ibid.

- Khyber Mail, October 25, 1936 op. cit.

- Abstract of Intelligence P. 382.

Source: World Scholars on Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Edited by: Ahmad Hasan Dani, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 1979.

Gandhi and Jinnah - a study in contrasts

An extract from the book that riled India's Bharatiya Janata Party and led to the expulsion of its author Jaswant Singh, one of the foun...

-

We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one State. ( Presidential Address to the Co...

-

Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creat...

-

Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the voice of one hundred million Muslims, fought for their religious, social and economic freedom. Through...