Jinnah and Islam

by Abdul Qayyum

One of the criticisms sometimes made of Jinnah (by Louis Fisher, for example) is that Jinnah was not a religious man. In this selection, Abdul Qayyum demonstrates how the problem of Jinnah’s alleged lack of interest in religion is handled in Pakistan. We are given a brief discussion of the characteristic of the Islamic reform movement led by Sayed Ahmad Khan (1817-1898) and Muhammad Iqbal (1873-1938), which helped to create some degree of consensus among “modernized” Muslims as to the significance of Islamic values for twentieth-century problems. Qayyum sees Jinnah as representatives of those who followed the reforms of Sayed Ahmad Khan and Muhammad Iqbal.

Sayed Ahmad’s efforts showed promise of success when, nearly six months after his retirement from service, Lord Lytton, Viceroy of India, performed the opening ceremony of the Muslim Anglo-Oriental College, Aligarh, on 8th January 1877. The M.A.O. College, which later grew into the famous Muslim University of Aligarh, imparted, through English as the medium of instruction, knowledge of western arts and sciences, together with instructions on Islamic thought and philosophy.

Sayed Ahmad filled the big void created in the life of the Muslim community by the disappearance of the Muslim rule. But he did more. His long life, spanning almost a century, bridged the gulf between the Medieval and the Modern Islam in India. Himself, a relic of the palmy days of the Great Mughals, he ushered in a new era. He gave the Indian Muslims a new prose, a new approach to their individual and national problems, and built up an organization which could carry on his work. Before this there was all disintegration and decay. He rallied together the Indian Muslims, and became the first prophet of their new nationhood.

*********************

For the next three years, Iqbal’s thought developed in the libraries of Cambridge, London and Munich. He studied philosophy at Cambridge, took his doctorate degree on the Development of Persian Metaphysics from Munich, and was called to the Bar in London. He studied the old masters of the East and the West, discussed philosophy and metaphysics with the renowned Dr. McTaggart, and conversed on literature and Islamics with Professors Nicholson and Browne.

*********************

It was Iqbal who was destined to play the historical role in the reconstruction of Islamic thought; he brought to bear upon Islamic institutions, which he respected no less than any Muslim of this time, a searching analysis of their fundamentals; he reinterpreted Islam as a dynamic rather than a static religion, and liberal rather than a reactionary force. In fact, in Iqbal’s view, Islam would cease to be Islam if its fundamentals were not living enough to allow a continuous process of fresh experiments and new adjustments to changes in society. It was the dynamic view of Islam that best fitted Iqbal for a happy synthesis of the East and the West in him.

The vision of a “new world” for the Muslims of the Indo-Pakistan sub-continent was projected by Iqbal when he acclaimed that the future of Muslims, with their distinct cultural and spiritual urges, lay in separate homeland. Presiding over the 1930 session of the Muslim League at Allahabad, he declared that he would “like to see the Punjab, the North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan, amalgamated into a single State….”

Iqbal was the first to see the vision of Pakistan. The role he played in promoting that intellectual revolution among the Muslims of the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent, which heralded the emergence of Muslims as a separate political force, conscious of their national destiny, decidedly constituted his most valuable contribution of the Muslim cause.

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah said about him: “To me Iqbal was friend, guide and philosopher, and during the darkest moments throughout which the Muslim League had to go, stood like a rock and never flinched for one single moment….Iqbal was the bugler of Muslim thought and culture. He was the singer of the finest poetry represents the true aspirations of the Muslims. It will remain an inspiration for us and for generations after us.”

Jinnah’s pre-occupation with political issues left him little time to devote himself to writing; but his speeches and sayings have been compiled by his admirers into a series of volumes, and they are all permeated with a liberal outlook.

Like Iqbal, Jinnah believed in Islam as a dynamic religion. “The discipline of the Ramzan fast and prayers will culminate today in an immortal meekness of the heart before God, “he said in a broadcast speech on Eid day, “but it shall not be the meekness of a week heart, and they who would think so are doing wrong both to God and to the Prophet, for it is the outstanding paradox of all religions that the humble shall be the strong, and it is of particular significance in the case of Islam; for Islam, as you all know, really means action. This discipline of Ramzan was designed by our Prophet to give us the necessary strength for action….”

Religion for Jinnah implied not duty to God, but to Mankind. “Man has indeed been called God’s caliph in the Quran, and if that description of man is to be of any significance, it imposes upon us a duty to follow Quran, to behave towards others as God behaves towards his mankind, in the widest sense of word, his duty is to love and to forebear. And this, believe me, is not a negative duty but a positive one. If we have any faith and love for tolerance towards God’s children, to whatever community they belong, we much act upon that faith in the daily round of our simple duties and unobtrusive pieties. It is a great ideal and it will demand effort and sacrifice. Not seldom will your minds be assailed by doubts. There will be conflicts not only material, which you perhaps will be able to resolve with courage, but spiritual also. We shall have to face them; and if today, when our hearts are humble we do not imbibe that higher courage to do so, we never shall.”

Whenever Jinnah got an opportunity to speak on religion, he advocated a rational approach. “In the pursuit of truth and the cultivation of beliefs,” he said, “we should be guided by our rational interpretation of the Quran, and if our devotion to truth is single-minded, we shall, in our own measure, achieve our goal. In the translation of this truth into practice, however, we shall be content with so much, as so much only, as we can achieve without encroaching on the rights of others, while at the same time nor ceasing our efforts always to achieve more. “In another context, he remarked: “The test of greatness is not the culture of stone and pillar and pomp but the culture of humanity, the culture of equality….and only a man who is dead to all the finer instincts of humility and civilization can call a religion based on determination and exploitation a heritage.”

Jinnah was outspoken in his condemnation of reactionary elements which generated retrograde tendencies in religion. Dealing with the contribution of the Pakistan movement to our national life, he said: “We have to a great extent to free our people from the most undesirable reactionary elements. We have in no small degree removed the unwholesome influence and fear of a certain section that used to pass off as Maulana and Maulvis. We have made efforts to make our women with us in our struggle….

He championed the cause of womanhood, advocating for women an equal share with men in social and national life. “In the great task of building the nation and maintaining its solidarity, women have a most valuable part to play. They are the prime architects of the character of the youth who constitute the backbone of the State. I know that in the long struggle for the achievement of Pakistan, Muslim women have stood solidly behind their men. In the bigger struggle for the building up of Pakistan that now lies ahead let it not be said that the women of Pakistan had lagged behind or failed in their duty.”

The liberalism of Jinnah freed the minds of the Indo-Pakistan Muslims, turning their intellectual activities towards tackling traditional Islamic ideas and ideals in terms of modern standards and requirements. Thus the final phase of the intellectual movement among the Muslims of the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent that was ushered in by Iqbal, began to be re-enforced by Muslim thinkers under the inspiring leadership of Mohammad Ali Jinnah. With the growing strength of Pakistan that phase is gathering momentum and spreading in every widening concentric circles, permeated with the spirit of both the Seer and the Leader.

Source: From Abdul Qayym, "Jinnah and Islam", in The Cultural Heritage of Pakistan, eds. S.M. Ikram and P. Spear (Karachi, 1955), pp. 186, 188, 192-193, 201-204. Copyright © 1955 by the Department of films and Publications, Government of Pakistan. Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press for the Department of Films and Publications, Government of Pakistan.

Quaid-e-Azam and Balochistan

by Dr. Munir Ahmed Baloch

The huge land mass of Balochistan rising steadily from the coastal plains of the sea of Arabia to the eerie heights of Quetta, and then descending in an undulating manner up to the fringe of the North-West Frontier Province, covers a little over 125,000 sq. miles constituting almost 43% of the total area of Pakistan. Another 45,000 sq. miles of Balochistan territory lie in the neighbouring state of Iran and smaller region in southern Afghanistan.1

With the advent of British colonial rule over India, Balochistan came under colonial influence in 1876 and was portioned among Iranians and the British. The Eastern part of Balochistan was further divided into British Balochistan, Balochistan States, while a part of Seistan was given to Afghanistan. The areas of Derajat and Jacobabad (Khan Garh) was demarcated and given to British India.

British imperialists used Balochistan as a military base to check the extension policy of Tsarist Russia against India.2 Balochistan was denied almost all forms of reforms which over the years, since the turn of the century, were introduced in other parts of India.

Despite being a separate administrative unit, Balochistan was not include in the list of provinces because it did not enjoy the status of a province. It was an administrative unit headed by the Agent to Governor General. This implied that the reforms introduced in the recognised provinces of British India were not introduced in Balochistan.3

The Quaid-i-Azam was aware of the vexing problems of Balochistan. He had demanded reforms in Balochistan in his famous “Fourteen Points”. He pleaded that Balochistan should be brought in the line with other provinces of India.

About the late twenties in Balochistan there were curbs on expression of open political opinions and there was no press. In 1927, Abdul Aziz Khurd and Nasim Talwi started a newspaper called “Balochistan” in Delhi. Yousuf Ali Khan Magsi, Sardar of the Magsi tribe, wrote an article for a Lahore newspaper in 1929 which he entitled “Fariad-e-Balochistan” or, “The Wail from Balochistan”. In May, 1939 he produced a pamphlet called “Balochistan ki Awaz”, or “The Voice of Balochistan”, specially for the British Parliament in London. In February, 1934, Yousuf Ali visited England in pursuit of his political objectives and both going and coming he visited Quaid-i-Azam at Bombay.

Muslim League was another political organization to sponsor the cause of Balochistan for the creation of a separate province for Balochistan.

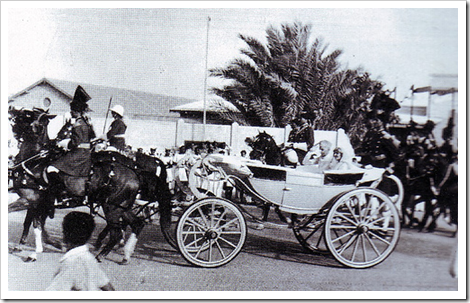

Apart from the other activities and visits of Muslim League leaders, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah himself visited Balochistan many times. In the middle of 1934, Quaid-i-Azam paid a visit to Balochistan and spent about two months there. In a public session of the League Conferences at Quetta, Qazi Isa made a dramatic and emotional gesture. Presenting the Quaid-i-Azam with a Sword, reportedly belonging to Ahmed Shah Abdali, he said:

Throughout history, the sword had been the constant companion of the Muslims. When the Muslims did not have an Amir, this sword was lying in safe custody. Now that you have taken over as the Amir of this nation, I hand over this historic sword to you. This has always been used in defence, in your safe hands also, it will be used only for this purpose.

In the memorandum, it was suggested, that “Balochistan is the right place for a considerable imperial garrison after the war. It was added that after the transfer of power in British India, “Balochistan” is not part of British India.” The memorandum was appreciated by Amry, as shown by his reply to Money on 18 November 1944 and his letter to Wavell, dated 23 November 1944.5

The Allies won the World War II on 2 September 1945. Ultimately, on 24 March 1946, the Cabinet Mission comprising three Cabinet Ministers arrived at Delhi presented the Partition plan of India on 16 May 1946. After the announcement of Paritition plan the tempo of political activity and polarization was between contending parties and factions gained momentum. Balochistan was of vital importance to the future of Pakistan as a country and people and, Mr. Jinnah was keen to make Balochistan a part and parcel of Pakistan. Conversely, the people who were averse to the prospect of the Indian Muslims securing an independent homeland, Nehru and Mountbatten, for instance, created all types of difficulties for the Muslim League. The foremost issue was: Which of the two Constituent Assemblies will Balochistan join, that is, of India or Pakistan. Moreover, that would be the status of Balochistan states on the lapse of British paramountcy? Would the leased areas be restored to the Khan of Kalat? What will be the future of the Princely States, their rulers and, so also that of the Tribal Territories in Balochistan?

The draft Proposal as revised by Cabinet Committee upto 8 May said:

In British Balochistan, the members of the Shahi Jirga other than those members who are nominated as Sardars of Kalat State, and non-officials members of the Quetta Municipality, will meet to decide which of the three options in para 4 above they choose. The meeting will also elect a representative to attend the Constituent Assembly selected.

Nehru objected to the proposal. He said:

It leaves the future of the Province to one man chosen by a group of Sardars and nominated persons who obviously represent a vested semi-feudal element. Baluchistan has an importance as a strategic frontier of India and its future cannot be dealt with in this partial and casual manner.

He added: “The future of Balochistan raised many strategic problems and the way at present envisaged is a very casual way of dealing with an important frontier area. Finally, he suggested that this case be deferred until the picture in the rest of India got clearer. This was not agreed to by the Viceroy”.

Whereas the Quaid-i-Azam emphasized that a democratic machinery might be devised to ensure free and fair expression of the will of the people, Mr. Liaquat Ali Khan, on behalf of the Muslim League, proposed a plebiscite. Any genuine democratic vote would satisfy the Muslims. He and the Quaid were very confident of winning Balochistan by the democratic method. They did not create any fuss, like Nehru.

Lord Mountbatten differed with both Jinnah and Nehru. He thought that in Baluchistan Tribal System, democratic mehhods would not work, and the prevailing system could not be altered in a haste.

Later His Majesty’s Government (HMG) revised the proposal and the revised draft was studied, and different proposals from the Quaid-i-Azam, Pundit Nehru and Sir Geoffery Prior, the Agent to the Governor General (AGG) in Balochistan, were put up to the HMG. Finally it was decided to hold a referendum in Balochistan on June 30, 1947 in Shahi Jirga excluding the Sardars nominated by the Kalat state and non-officials members of Quetta Municipality. That would decide the future affiliations of Balochistan.

An extraordinary joint Session of the Shahi Jirga was held on 30 June 1947 to decide the crucial issue. To the dismay of the Congress, 54 members of the Shahi Jirga and Quetta Municipality, voted en-bloc to join the new Constituent Assembly to be set up in Pakistan.

The credit, in a large measure, for the convincing success of the Muslim League in these circumstances goes to Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah and the Balochistan Provincial Muslim League who successfully countered the Congress propaganda.6

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s role, first as the Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim Unity, and subsequently as the leader of the Muslims, during 1936-1947, supported the cause of Balochistan and demanded accession from the Khan. Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah regarded Balochistan as his last resort in case of the failure of the demand for Pakistan.

With the lapse of the British paramountcy in 1947, the Khanate of Balochistan became an independent sovereign state. The Khan, Mir Ahmad Yar Khan, announced independence in a public speech on 15 August 1947. Soon after the promulgation of the constitution, elections were held at the Kalat state National Party won 39 out of a total 51 seats on Lower House. The rest of the seats went to independent candidates, who supported the cause of the National Party.

On 13, December, the Khan summoned the Lower House to discuss, the official language, the Sharia (Islamic Law), and relations between the Khanate of Balochistan and Pakistan, with special reference to accession.7

In September 1947, the Prime Minister of Kalat, Nawabzada M. Aslam, and the Foreign Minister, D.Y. Fell travelled to Karachi to discuss the leased areas, under the Kalat-Pakistan Agreement of August 1947. The meetings between the officials of the two states were not fruitful, due to policy of the Pakistani Government, which insisted on an unconditional accession of the Khanate to Pakistan. On 20 September 1947, Mr. Ikramullah, the Pakistan Foreign Secretary wrote a letter to Aslam, the Prime Minister of Khanate, urging the accession of the Khanate and, meanwhile, the president of the British Balochistan Muslim League, Qazi M. Isa, met the Khan and conveyed to him a message from Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the Governor-General of Pakistan, who extended an invitation for the Khan to come to Karachi to discuss future relations between the Khanate and Pakistan. Before the Khan’s visit to Karachi in October 1947, he discussed all possible courses of action with his Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister.

The Khan went to Karachi on Jinnah’s invitation with a draft treaty which he wanted to use as a basis for negotiations with the Government of Pakistan. The draft treaty proposed by the Khan was aimed at entering into a treaty relationship with Pakistan.8

On his arrival in Karachi, the Khan was not received by the Governor General nor by the Prime Minister, because Jinnah advised him to accede the Khanate to Pakistan and stated that he could propose no better course than accession.

Nevertheless, the Khan refused the demand of Mohammad Ali Jinnah and said, “As Balochistan is a land of numerous tribes, the people there must be consulted in the affairs prior to any decision”. The Khan promised Jinnah to reply after consulting the parliament of the Khanate. On December 12, 1947, a Session of the Darul-Awam was summoned by the Khan to discuss the matter of accession. The house after a debate adopted the following resolution unanimously on December 14, 1947.

Relations with Pakistan should be established as between two sovereign states through a treaty based upon friendship and not by accessions.

On January 4, 1948 the Darul-Umra also passed the same resolution. The Prime Minister Aslam visited Karachi with a copy of the proceedings of the parliament. He met Jinnah and discussed the matter of accession. On his return to Kalat in February, he brought a letter from Jinnah, dated 2 February 1948, addressed to the Khan. In this letter, once again Jinnah repeated the demand to join Pakistan.

On February 11, 1948, Quaid-i-Azam came to Sibi, situated in former British Balochistan, where a meeting was arranged between the Khan and Jinnah on the evening of the following day. On the 13, they had a second meeting at Dadar—the winter capital of the Khanate. Another meeting fixed for the 14th, had to be cancelled due to the sudden “illness” of the Khan.

Jinnah was disappointed by the behaviour of Khan and his parliament. On March 9, 1948, it was communicated to the Khan that “His Excellency had decided to cease to deal personally with Kalat state negotiations, to decide the future relations of Pakistan and Kalat.” Col. S.B. Shah was assigned to deal with the Khanate’s affairs, with the help of Aslam, who knew the internal conflicts and rivalries among the Khan and his chief, including feudatory chiefs, Mir Bai Khan, Gichki, Nawab of Mekran (Brother-in-Law of Khan) Ghulam Qadir, Jam of Las Bela, and Mir Habibullah Nusherwani, Nawab of Kharan. They met Jinnah on 17 March 1948, and informed his that “if Pakistan was not prepared to accept their offer of accession immediately they would be compelled to take other steps for their protection against the Khan of Kalat’s aggressive actions.”

After their meeting with Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s Cabinet met in an emergency session discuss the request the chief of Balochistan. The cabinet decided to accept the offer in order to put pressure on the Khan for accession. On 17 March Jinnah accepted the accession.

On 18 March, the Pakistan Minister of Foreign Affairs issued a press Statement, announcing that Pakistan had accepted the accession of Mehran, Kharan, and Lesbela, with the “accession” of these areas, Kalat lost its connection with Iran and Afghanistan and was left without any outlet to the sea.

After the accession of these states. The Joint Secretary for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Col. S.B. Shah approached the Baloch chiefs Wadera Bangulzai, Sardar Shahwani, Sardar Sanjarani, and offered them an autonomous status if they accede to Pakistan. Meanwhile Sardar Raisani offered his cooperation to Col. Shah.9

Nevertheless, the Khan saw two alternatives:

- To leave the palace and to take refuge in the mountains in order to fight.

- To accept the demand of accession.

The first alternative was opposed by Fell, and supported by nationalists. Khan agreed with proposed of Mr. Fell and saw the “wisdom” of declaring “accession”, without the approval of the parliament. On 28 March 1948, he informed the Government of Pakistan about his decision and the Khanate became a part of Pakistan.10

Notes and References

- Ahmad Abdullah, The Historical Background of Pakistan and its people. (Tanzem Publishers, Karachi, 1973), p. 72

- Stephanie Zinged, Pakistan in the 80’s: Ideology, Regionalism, Economy, Foreign Policy, (Vanguard, Lahroe 1985), pp. 336-37.

- Riaz Ahmad, “Quaid-i-Azam’s role in the London Round Table Conference 1930-31” Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol. I, No. 1 (Spring 1995), p. 20.

- A.B. Awan, Balochistan Historical and Political Processes, (New Century Publishers, London w. 1985), p. 20.

- Inayatullah Baloch, The Problem of Greater Balochistan, A Study of Baloch Nationalism (GMBH Stallgart, 1987), p. 174.

- Lt. Col. Syed Iqbal Ahmed, Balochistan: Its Strategic Importance (Royal Book Company, Karachi, 1992), pp. 109-112.

- Inayatullah Baloch, op. cit., pp. 175-76.

- Ibid., pp. 181-182.

- Ibid., pp. 183-187.

- Ibid. p. 189.

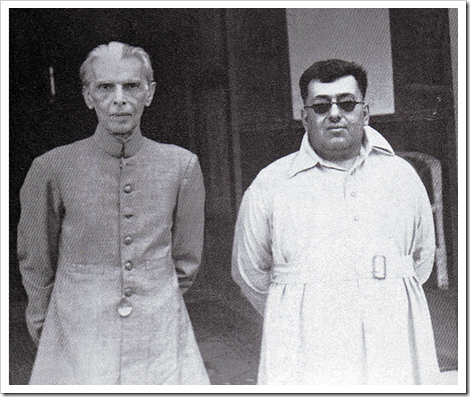

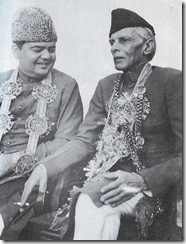

Quaid-e-Azam with A K Fazlul Haq

A K Fazlul Haq popularly known as the lion of Bengal, Haq proposed the Pakistan Resolution on 23 March 1940

Gandhi and Jinnah - a study in contrasts

An extract from the book that riled India's Bharatiya Janata Party and led to the expulsion of its author Jaswant Singh, one of the foun...

-

We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one State. ( Presidential Address to the Co...

-

Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creat...

-

Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the voice of one hundred million Muslims, fought for their religious, social and economic freedom. Through...